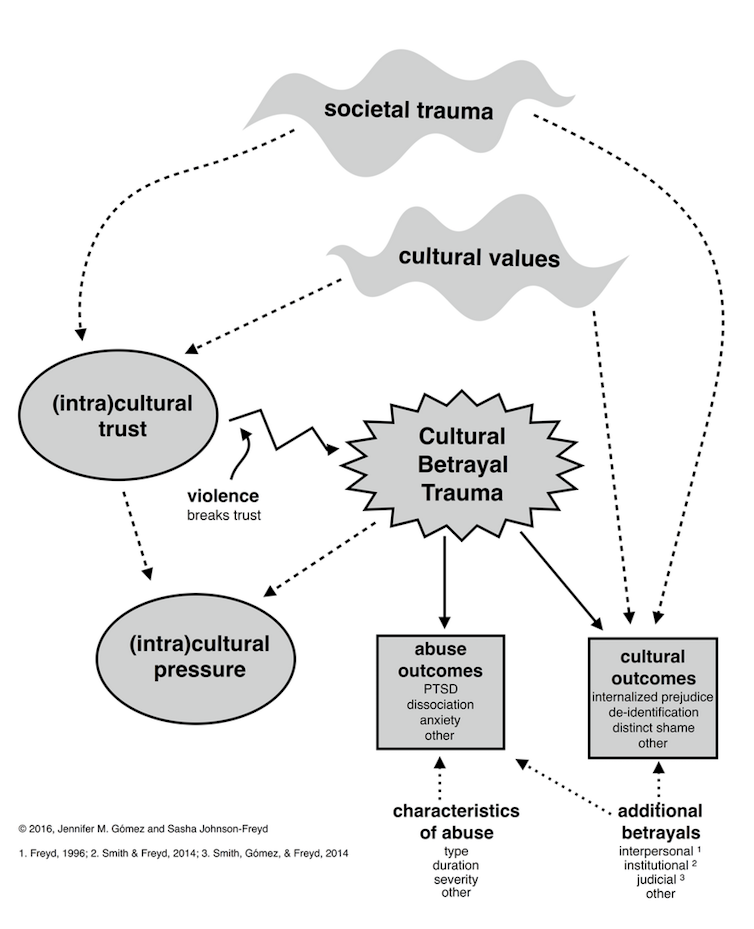

Dissociation is most common in trauma that involves a betrayal of trust. This is a survival mechanism that protects our need for social support.

Sober October has ended and now (hopefully sober) November begins. Fall brings the annual three-fold challenge: Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s. This year, the midterm elections have created a fourth stressor and some of us are barely muddling through. Recent events have been especially terrifying—mass shootings, pipe bombs, a new report of catastrophic climate change, and the ongoing nightmare that is the Justice Department’s current mandate.

Recently, Senator Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) called for an investigation into allegations made by Julie Swetnick—one of the brave women who accused Brett Kavanaugh of sexual misconduct. Unbelievably, Grassley ordered the FBI to open a criminal investigation—into Swetnick.

Grassley said that Swetnick’s sworn affidavit was not true. Was this just his opinion? It wasn’t based on FBI reports because he and fellow Republicans would not allow the feds to thoroughly investigate her claims against Kavanaugh—nor anyone else’s.

“During the years 1981–82,” Swetnick said in her sworn statement, “I became aware of efforts by Mark Judge, Brett Kavanaugh and others to spike the punch at house parties I attended.” She also stated, “In approximately 1982, I became the victim of one of these gang or train rapes where Mark Judge and Brett Kavanaugh were present.” Swetnick said she’d seen Kavanaugh drink excessively at these parties and described him as a mean drunk.

CBS News video:

The Brett Kavanaugh Hearing

In late September, Kavanaugh accuser Dr. Christine Blasey Ford went before the U.S. Senate during Kavanaugh’s SCOTUS confirmation process. There were times during her testimony that I felt sick to my stomach. It was as if she were telling my story. Dr. Ford stated that some of her memories were seared into her mind. She also acknowledged that she wasn’t able to recall every detail from that day. But who remembers every detail of any event?

It was reassuring when Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vermont) acknowledged this:

“Ford has at times been criticized for what she doesn’t remember from 36 years ago. But we have numerous experts, including a study by the U.S. Army Military Police School of Behavioral Sciences Education, that lapses of memory are wholly consistent with severe trauma and stressful assault.”

But the Republicans were not interested in further investigation and, despite the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements and all of the highly publicized Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby survivors, much of the country remains obtuse when it comes to the shared traits of traumatized women: remembering some things but not others, and not telling anyone what happened to them for decades.

Ford’s assault happened at a party when she was 15, in 1982. When I was 13 I was gang-raped by classmates at an outdoor gathering. Ford tried to forget what happened. So did I. She didn’t want to think about the worst night of her life. Neither did I. It took both of us decades to tell anyone. Ford said: “I convinced myself that because Brett did not rape me, I should just move on and just pretend that it didn’t happen.” Confused and freaked out, I, too, decided to pretend my rape didn’t happen and believed that would “erase” it.

Ford told the committee: “I tried to yell for help. When I did, Brett [Kavanaugh] put his hand over my mouth to stop me from yelling. This is what terrified me the most, and has had the most lasting impact on my life. It was hard for me to breathe…. Both Brett and [his friend Mark Judge] were drunkenly laughing during the attack.”

Through much of the hearing I was shaking and sobbing, wiping my eyes so I could see. The identification triggered the sensation that I was reliving my experiences. When she said her mouth was covered, it felt as if mine was, too. I felt like I couldn’t breathe. The laughter from the boys that hurt me is burned into my memory. When I went public with my story in January 2012, I wrote: “[My friend] grabbed me, clamped his hand over my mouth….I tried to scream but it came out muffled. They laughed. I gagged.”

I became so upset watching the live video that I almost called a close friend. I stopped myself because I knew she’d say, “Stop watching it!” Inspired by Ford’s bravery, I felt a sisterhood during this historical moment. It felt like my duty to bear witness.

During the hearing, Senator Feinstein addressed Ford: “You were very clear about the attack. Being pushed into the room, you say you don’t know quite by whom, but that it was Brett Kavanaugh that covered your mouth to prevent you from screaming, and then you escaped. How are you so sure that it was he?”

Ford responded: “The same way that I’m sure that I’m talking to you right now. It’s just basic memory functions. And also just the level of norepinephrine and epinephrine in the brain that, sort of, as you know, encodes—that neurotransmitter encodes memories into the hippocampus. And so, the trauma-related experience, then, is kind of locked there, whereas other details kind of drift.”

Alcohol Blackouts

The second half of the Senate hearing was shocking. Who but an alcoholic would mention beer nearly 30 times in a job interview? This was to determine if Kavanaugh was right for a lifetime position on the highest court. He whimpered, cried and lashed out. Did baby need his bottle? When Sen. Klobuchar asked if Kav ever had a blackout, he responded, “Have you?” Twice.

Video clip of that part of the Kavanaugh Hearing:

A few days after the Kavanaugh hearing, still feeling wrecked, I reached out to neuroscientist Apryl Pooley, PhD, an expert on the brain and memory and the author of Fortitude: A PTSD Memoir, which documents her road to healing from rape, child abuse, PTSD, and addiction.

Both Dr. Pooley and I were blackout drinkers. We discussed how unpredictable alcohol is. In my teen years, I blacked out if I drank too much too quickly or hadn’t eaten. But in the last few years of rum and cocaine, I could go into a blackout after one gulp, or I could guzzle 5-6 drinks and feel totally sober. Pooley said her experiences were similar.

But both of us found it difficult to believe that Kavanaugh was telling the truth at the hearing. It’s possible he didn’t know that he blacked out, but that is highly unlikely. After many of my drunken binges, friends would refer to things I’d said or done that I had no memory of. When I asked them if everybody knew I was that drunk, they’d say no. “You seemed normal, maybe a little high.”

Pooley said, “I’d be walking around and having conversations. People wouldn’t know if I was blacked out. When someone is blacked out, it means their blood alcohol level is so high that it’s impairing that part of their hippocampus, that part of your brain that encodes those memories.”

She said that everything you’re doing and seeing may or may not be getting stored in your brain. I asked her about being in and out of consciousness. Sometimes I could remember a snippet of an evening. Chatting with a friend at a bar, but then I had no idea how I got home.

“That’s called a fragmentary blackout,” she said, “or a brownout. That happens when you are blacked out for a while and then come out of it. That can mean that you’d metabolized some of the alcohol, enough of it to regain that function.”

She also said that some people might think a blackout means passed out or unconscious, which can also look like you’d just fallen asleep.

Blackouts from Trauma

According to Pooley, Ford was correct when she spoke about how the brain and memories work. Ford stated that a “neurotransmitter encodes memories into the hippocampus” which explains that trauma-related experience can be “locked in” whereas other details can “drift.”

Pooley expanded on that: “When recalling memories of trauma, they can pop into your head if you’re triggered, or when asked about a detail.”

That reminded me of every episode of Law & Order: SVU. Olivia Benson always asks a traumatized victim specific questions: What did they look like? What were they wearing? Can you remember anything unusual? A logo on a hat, shirt or vehicle? The sound of their voice? What they said?

“Right!” said Pooley. “Those questions can trigger a flashback. The survivor may remember details about the event but not be able to verbalize them. To an outsider, this may look like they don’t remember or are lying. If the survivor was dissociated at the time of the assault, when they remember it later they may seem surprised or confused at their own memory.

“If survivors feel unsafe when questioned, they may not be able to use their pre-frontal cortex to understand the questions and retrieve certain memories. That’s because their brain was focused on survival. If triggered, they may experience emotional and sensory memories that are as intense as the trauma itself.”

Aha! That’s why I was shaking and crying while watching the Kavanaugh hearing. And for days afterward. The PTSD had caused my body to react by reliving what happened to me.

Research backs up Ford and Pooley’s explanations. Memories may be fragmented and certain details missing.

“But,” Pooley said, “what the survivor does recall is incredibly accurate. Sometimes you hear the term ‘repressed memories,’ which is probably more accurately referring to memories that were stored during dissociation. Dissociation is a survival reflex that can occur when escape is—or seems to be— impossible. A threat may be perceived by the brain as inescapable because of a physical barrier.”

Ford was afraid she was going to die when she described Kavanaugh’s hand over her mouth. In my case, dissociation happened when I was pinned by five guys. I’d tried to break free. I floated up to the trees and watched. I could see what the boys were doing to me but it took on a surreal quality. It served as a buffer. I was literally scared out of my mind and my body.

“A threat can also be perceived by a psychological barrier,” said Pooley. “Dissociation is most common in trauma that involves a betrayal of trust. This is a survival mechanism that protects our need for social support. When the trusted individual betrays you, this is a social threat and social threats are real threats.”

Ford and I both experienced that. She’d gone to what she expected to be a friendly party with people she knew. I thought the guy who tricked me was my friend. He said he wanted my advice about his girlfriend. Flattered, I practically skipped over. That’s when he clamped his hand over my mouth and threw me to the ground and the other boys surrounded me and held me down.

Pooley explained: “Many people believe that life-threatening trauma only refers to threats to physical safety—like the presence of a weapon—but humans need social support for survival. So, social threats like bullying, ostracization, or anything that threatens social standing can be interpreted by the brain as life-threatening. If abuse or assault is perpetrated by a trusted individual, not only is the event traumatic, but the social threat of losing the sense of safety from that person [or people] is traumatic as well.”

If trauma leads to dissociation, Pooley said, that can lead to amnesia. Traumatic amnesia is so common that it’s even included in the diagnostic criteria for PTSD.

“When all or part of the traumatic experience cannot be remembered,” said Pooley, “the risk for developing PTSD greatly increases.

Throughout the hearing, and frankly, throughout these past few years, I’ve often felt an overwhelming temptation to get high. My mind and body are so wound up that I crave some kind of relief. Rum and cocaine still hover in my mind, pretending to offer salvation. Thankfully my years in recovery have taught me not to listen to my head when it’s trying to get me high, not to keep secrets, and to make time to meditate, keep a journal, draw, hug my dog, and most importantly, remember to breathe.

If you are shaken by the Kavanaugh Hearing, and especially if it has kicked up flashbacks, there is help. The same is true for anyone who is scared about the midterm election or having panic attacks and high anxiety.

You can reach out to RAINN, the nation’s largest sexual violence organization. Their website is RAINN.org or you can call their hotline 24/7 at 800-656-HOPE. For any kind of mental health help including addiction, PTSD, or thoughts of harming yourself please visit the National Alliance on Mental Health’s list of hotline resources.

View the original article at thefix.com