Would we be able to reach across the distance—and our failings—to touch each other, to smile?

We’re together for the first time in five years, the three of us. Three sisters. Terry, the oldest, pastes us together with persistence and illusion. She believes we can be a family, that we are a family. Julie, the youngest, bites her lower lip and wears a worried brow, even while she drives her red Miata with the top down to her job as a South Carolina attorney. She left home for law school fifteen years ago and comes back only for weddings or other landmark celebrations like this, or for Christmas every two years. And me, in the middle. I moved to Connecticut almost twenty years ago to cut free from my tangled roots, I thought, and to be near the hospital where I learned to stop drinking and to want to live again.

I suspect my newest illness—Chronic Fatigue Syndrome—structures my life in a way my family must find limiting. At least that’s what I think when I hear their voices in my head. You’re tired all the time? Go to bed earlier. You can’t think straight? You’re an Ivy League graduate, for heaven’s sake. Start jogging again. You’ll feel better.

But when I’m tucked away, writing in the pretty place on Long Island Sound I call home, half an hour from Manhattan, surrounded by people who drive German and Italian cars and wear Prada and Polo, I pretend their success is mine and that my medical bills and dwindling bank accounts and lost jobs and derailed relationships don’t much.

When I return Upstate to the tricky terrain on chilly Lake Ontario, though, my creative ambitions seem paltry and a little suspect. I feel I’ve failed. But, I remind myself, I’m thin. And I used to have enviable, respectable jobs. And I saw the Picasso exhibit at the Met. I hang onto those vanities like life preservers tossed to me in rough seas.

We’re together to celebrate our mother’s birthday, her seventy-fifth. Each of us brings her gifts to the party. Collectively, we also bring 130 years of survival skills, learned, not on some Outward-Bound wilderness adventure with a trusted coach, but in this family, where I, at least, believed no one was to be trusted.

*****

For three weeks, we made plans. When I called to ask Terry what I could contribute to the buffet, she discouraged me from bringing anything other than Tom. “As for sleeping arrangements,” she mused. “I’ll put Julie and Ken in the guest room. You can sleep in Katie’s room, and Tom can take the den.” She paused. “But the pullout sleeps two if you want to stay with him.”

Terry and I have been sisters for forty-four years. We emerged, screaming, flailing, from the same womb, played hide and seek in the same neighborhood, suffered algebra in the same high school. But before that clause (“. . . if you want to stay with Tom.”), we never talked about touching men or sleeping with them. When I hung up and told Tom about this tender talk between my sister and me, I was baffled when he said, “I guess they think I’m okay.” How could he shape so private a moment between Terry and me into something about him? But I shook off his self-absorption. He’s not Catholic. He wasn’t raised in a home where no one touched without wriggling to get free. And he doesn’t know how important it is to try to get to know your sister when you’ve spent three decades shoring up the distance from her and you’re no longer sure why.

When I called Julie, she railed because Terry decided the party date and time without asking her. “Why did I offer to help if she’s taking care of everything?”

I’m the middle sister. I’m in the middle, again and always, but I welcomed Julie’s rant. Any connection would feel better than the unexplained plateau we tolerated between us since her marriage ten years earlier. “I don’t know what to wear,” she said, trying to regain her equilibrium.

“Pants and a sweater maybe,” I posited gingerly, not wanting to sever the tentative thread between us. “April’s still winter upstate.”

“I might need something new.” The thought of a shopping mission jumpstarted Julie’s party stride. “They’re all on special diets,” she said, “so we’ll need to make sure everyone has something to eat. Dad can’t have nuts, remember?”

* * * * * *

Tom and I set out late Friday morning, my mood dipping as we rode the thruway into Rockland County and beyond. The sky hung as heavy and gray as it did six months ago when we went home for Thanksgiving, me with the same faint hope. Maybe this time things will be different.

When we pulled into Terry and Bill’s driveway five hours later, stiff from sitting, Dad rushed to the door, his hair whiter and thinner. For a moment I mistook him for his father. And before he hugged me, I remembered that one Father’s Day brunch, when my father raged at his father because Grandpa couldn’t hear the waitress when she rattled off the holiday specials. “Stop!” I yelled. Why did I need to tell him to stop hurting his father? All I wanted was to be his favorite girl.

His favorite girl? A dicey proposition. “How’s my favorite girl?” he’d ask when he hustled in, late—again—for dinner.

“We don’t have favorites,” Mom was quick to point out as she slid a reheated plate across the table to him.

Stop. I pulled myself back to Terry’s foyer. We hadn’t yet said hello, and I had dredged the silt of the River Past. Say hello. My father hugged me tight—he at least was generous with his hugs, though from him they never stopped feeling dangerous. We don’t have favorites. Although I hugged back, I stiffened in his arms and drew away too quickly. “You remember Tom?” Then I kissed Mom who, smaller than she used to be, still held her affection in reserve. “Hi, hon.”

“You made it.” Terry said, smiling as she came in from the kitchen, wearing a gingham apron over her Mom jeans. “How was the drive?”

As soon as I answered— “An hour or two too long”—I wondered if she thought my words meant I didn’t want to be there. We attempted a hug, and I held on a little too long, searching for something bigger, warmer, because in her stiffness, I heard questions. Is she angry because I don’t do my share? (Who wouldn’t be?) That she’s the one who drives Dad to his cataract surgery and perms Mom’s hair? (Of course, she’s angry.)

“Nice outfit,” she said, and I resisted suggesting a livelier hair color for her.

When Terry offered her cheek for a quick kiss, I saw Julie at the edge of the foyer, half in, half out, arms crossed. “You look great,” I said, hoping to breathe a little fire into her. “Hi.” She stretched the one syllable to two, an octave higher than her normal speaking voice, trying to sound different than she looked, as if she were frozen, unable to come closer.

Hungry?” Terry asked.

“Starved,” I said, not letting on that, more than food, I wanted a belly full of comfort.

Tom and I brought in the dinner fixings—ravioli and salad greens I bought at Stewart’s market, bread and cheesecake from Josephine’s bakery—and Terry, Julie and I set about making the meal. Before Terry lifted the lid from the cooking ravioli, I knew she would sample one before she pronounced, “They’re done.” Then she would wrap the dish towel around the pot so she wouldn’t burn herself when she lifted it from the stove and dumped the steaming pasta into her twenty-year-old stainless colander with the rickety feet in the sink.

I knew, too, how Julie would stand at the counter, her shoulders sloping forward, while she diced tomatoes and chopped garlic.

I knew their rhythms, their postures, but I wanted to reach to them, to ask them please, would they look at me, would they be my friends. Instead, I wondered why it seemed so hard to say something spontaneous, or to laugh from our bellies.

“Stewart’s was so crowded when I shopped, I had to meditate to steady myself when I got home, even before I unloaded my bags.”

They turned to me when I took a stab at something genuine, but their tilted heads, their uncomprehending eyes signaled they didn’t know know how post-shopping meditation worked or why it should be necessary.

“How are the grocery prices in Connecticut?” Terry asked, and my hope for connection vaporized as rapidly as the steam rising off the ravioli.

*****

Party day. Relatives arrive from across the county. My cousin, Peter, the accountant, the one I was sure, when I was six, I would marry, with his wife, Marie, still perky, still chatty, still in love. My teacher cousin, Patricia, with her professor husband, Art, who sports a ponytail and more stomach than when I saw him last. Janice, married to Cousin Dave, squints as she walks in the door. “Madeleine?” She needs time to adjust to the light. “It’s been fifteen years!” She stretches out her arms and hugs me the way I want my sisters to hug me. “I’ve missed you.”

One cousin, Karen, the one who took too many pills ten years ago, isn’t here. But her brothers are, and I feel like a part of them should be missing because their sister is dead. As if maybe each of them should be minus an ear or a hand, some physical part because Karen died. How is it you two are here when your sister isn’t?

My uncles walk in, proud of their new plastic knees and hips. Here are my aunts, who shampooed my hair with castile soap, taught me to bake Teatime Tassies, and let me dress up in their yellowed wedding dresses in their dark attics. Each of them hobble-shuffles in, looking a little dazed by all the fuss.

For almost twenty years, I kept my distance from these relatives, these potential friends, visiting every year or so for a day or two of polite, disingenuous conversation. I needed to banish myself, I suppose. After all, there was the drinking, and the fact that I hadn’t amounted to much, given all that potential they all told me I had. But at this party I look them in the eyes when I talk, trying to recover a little of what I lost by staying away. Uncle Frank tells me my maladies must emanate from some emotional twist, or from the fact that I’m alone, away from my family. Like a working man’s Gabriel Garcia Marquez, he confides magically real stories about men from the factory who went blind from jealousy or ended up in wheelchairs from unexpressed fears. “Why don’t you come home, honey?” Home? Is this still my home? Was it ever?

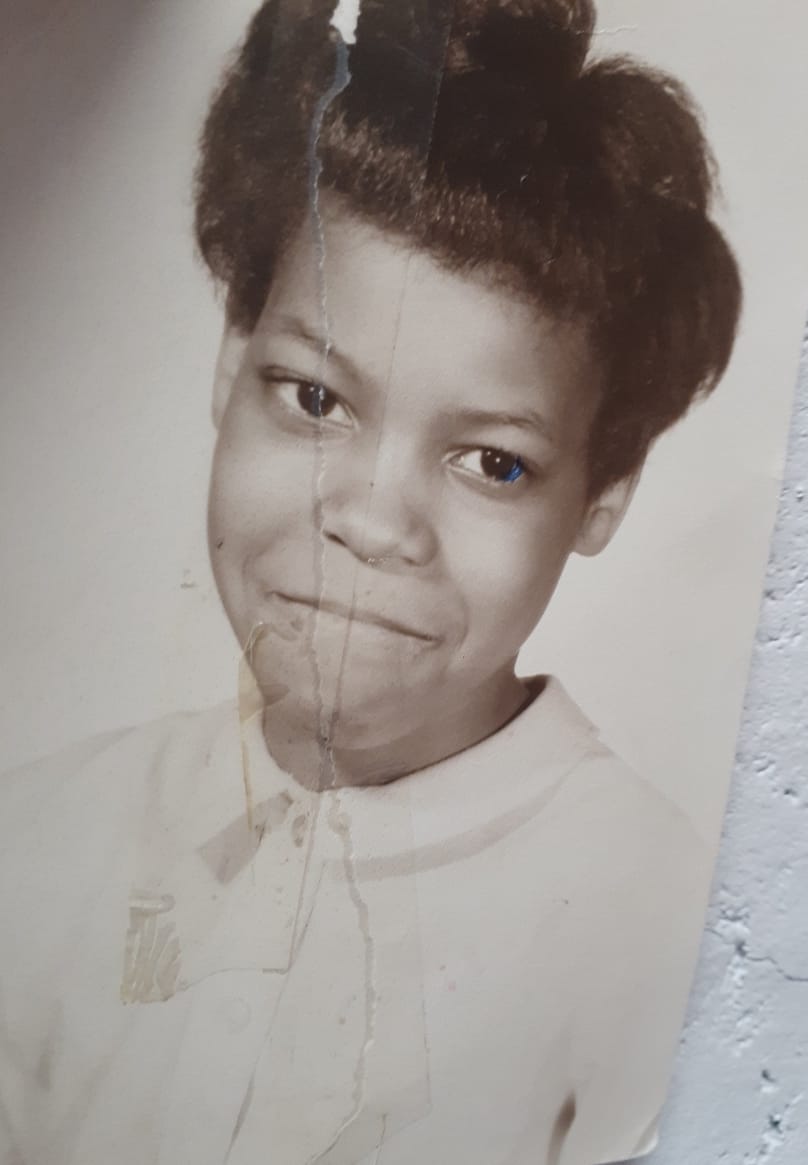

There’s a lot of red in this house, I notice, when I scan the crowd. Except for Terry, whose hair still imitates the non-offensive light brown we were born with, each of us female cousins wear some shade or other of red hair: medium red beech; burgundy berry; Cinna berry; sunset blonde. And though my mother and her two sisters didn’t plan this, each of them is in red: tiny Aunt Emma in the knit dress she wore for last year’s Christmas portrait with her ten grandchildren; Aunt Anna in a red and black striped twinset with a black skirt; and Mom in a red blazer and skirt. They sit on the couch, one wearing a strand of pearls, another a locket, the other her “good” watch because this is a special occasion.

All this red surprises me. We’re not what you’d call a red family. We may glower underneath; but as a rule, we don’t flare or flame. The Slavic temperament prefers to smolder chalky gray, while the red burns beneath the surface.

They look too small, these women, sitting next to each other, after I ask to take their picture. And there’s too much distance between them. I want them to scrunch together—which they won’t—so they seem closer.

No matter how far apart, though, it’s important that these three little women are together on this sofa, posing. Aunt Anna never used to let us take her picture. But maybe, like me, she knows there is something final about this portrait. Each of them is ill. Aunt Emma is diabetic; and, although we don’t yet know this, a cancer is growing in her left breast, just above her heart. Aunt Anna’s Parkinson’s disease is progressing, and Mom has a bad heart. I don’t know these specifics as I see these three women through my lens, but I know it’s inevitable. Something will happen to them soon.

The flash goes off on my camera. Once. Twice. “That’s it.” Aunt Anna waves me away with her shaky arm. “Enough pictures.” She pushes herself off the couch and turns on the television to watch a golf tournament. The moment is over, but I have it on film, and in my heart.

*****

Mom is failing, Cousin Pat wrote in her holiday note about Aunt Emma. And when I called Aunt Anna on Christmas, she told me how she fell three times during the last month and Terry confirmed that, like Aunt Emma, Aunt Anna was failing.

My father didn’t use the same word to describe my mother. Failing wasn’t a word that would come easily to him. But he apprised me in detail about Mom’s last neurologist appointment, when she would see him next, how he would adjust her medication schedule: eight in the morning, noon, four in the afternoon, and seven-thirty at night. I admired the way he structured her care. But when he barked at her to come to the phone, my stomach gripped. I worried he might be hurting her.

After hanging up, I reached for the portrait of my mother and her sisters. I wondered. In twenty-five years, when my sisters and I are smaller, when we sit together for a picture on Terry’s seventy-fifth birthday, how much space would hang between us? Would we be able to reach across the distance—and our failings—to touch each other, to smile? I didn’t know. But I knew this: if I hoped to touch them in the future, I needed to reach to them now, as they are, not as I would have them be.

Terry and Julie and I won’t sit for a portrait on Terry’s seventy-fifth birthday. She left us last year, victimized by a rare immune disorder, when she was sixty-two. So, there will be no photo. Only the memory of wanting one. And the hope, too long postponed, that the distance between us would narrow if we only reached to one another, even if just a little.

View the original article at thefix.com