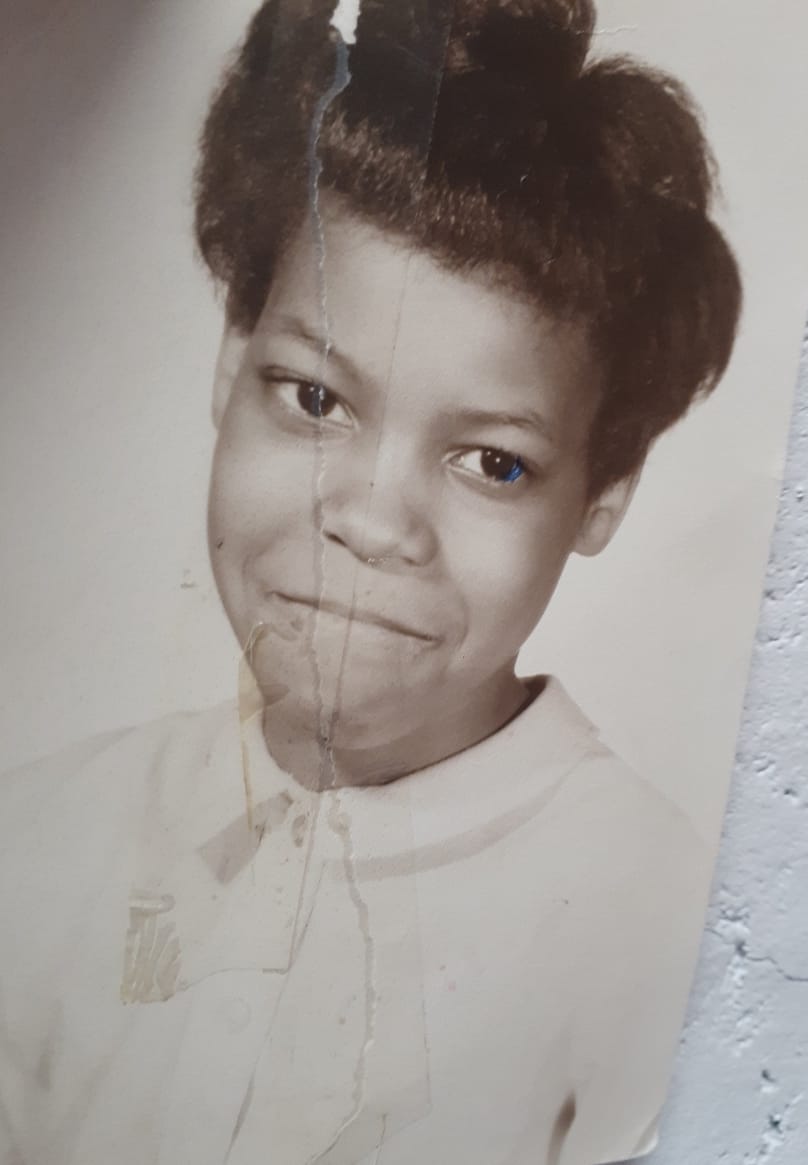

Although Gloria experienced trauma, violence, and institutionalized oppression, she never gave up hope. Now, in recovery, she is a counselor and staunch recovery advocate.

True recovery is the healing of the human spirit.

It is a profound recognition that we not only have the right to live

but the right to be happy, to experience the joy of life.

Recovery is possible if only you believe in your own self-worth.

-Gloria Harrison

Although the dream of achieving recovery from substance use disorders is difficult today for people outside of the Caucasian, straight, male normative bubble, there is no question that progress has been made. If you want to know how difficult it was to get help and compassionate support in the past, you just have to ask Gloria Harrison. Her story is a stark reminder of how far we have come and how far we still must go.

As a young gay African American girl growing up in a Queens household overrun with drug abuse and childhood trauma, it is not surprising that she ended up becoming an addict who spent years homeless on the streets of New York. However, when you hear Gloria’s story, what is shocking is the brutality of the reactions she received when she reached out for help. At every turn, as a girl and a young woman, she was knocked down, put behind bars in prisons, and sent to terribly oppressive institutions.

Gloria’s story is heartbreaking while also being an inspiration. Although she spent so much time downtrodden and beaten, she never gave up hope; her dream of recovery allowed her to transcend the bars of historical oppression.

Today, as an active member of Voices of Community Activists & Leaders (VOCAL-NY), she fights to help people who experience what she suffered in the past. She is also a Certified Recovery Specialist in New York, and despite four of her twenty clients dying from drug overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic, she continues to show up and give back, working with the Harlem United Harm Reduction Coalition and, as a Hepatitis C survivor, with Frosted (the Foundation for Research on Sexually Transmitted Diseases).

Before delving into Gloria’s powerful and heartbreaking story, I must admit that it was not easy for me to decide to write this article. As a white Jewish male in long-term recovery, I was not sure that I was the proper person to recount her story for The Fix. Gloria’s passion and driving desire to have her story told, however, shifted my perspective.

From my years in recovery, where I have worked a spiritual program, I know that sometimes when doors open for you, it is your role to walk through them with courage and faith.

A Cold Childhood of Rejection and Confusion

Like any child, Gloria dreamed of being born into the loving arms of a healthy family. However, in the 1950s in Queens, when you were born into a broken family where heavy responsibilities and constant loss embittered her mother, the arms were more than a little overwhelmed. The landscape of Gloria’s birth was cold and bleak.

She does not believe that her family was self-destructive by nature. As she tells me, “We didn’t come into this world with intentions of trying to kill ourselves.” However, addiction and alcoholism plagued so many people living in the projects. It was the dark secret of their lives that was kept hidden and never discussed. Over many decades, more family members succumbed to the disease than survived. Although some managed to struggle onward, addiction became the tenor of the shadows that were their lives.

Gloria’s mother had a temper and a judgmental streak. However, she was not an alcoholic or an addict. Gloria does remember the stories her mother told her of a difficult childhood. Here was a woman who overcame a terrifying case of polio as a teenager to become a singer. Despite these victories, her life became shrouded in the darkness of disappointment and despair.

In 1963, as a pre-teen, Gloria dreamed of going to the March on Washington with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. Her mother even bought her a red beanie like the militant tam worn by the Black Panthers. Proudly wearing this sign of her awakening, Gloria went from house to house in Astoria, Queens, asking for donations to help her get to Washington, D.C. for the march. She raised $25 in change and proudly brought it home to show her mother.

Excited, she did not realize it was the beginning of a long line of slaps in the face. Her mother refused to let her little girl go on her own to such an event. She was protective of her child. However, Gloria’s mom promised to open a bank account for her and deposit the money. Gloria could use it when she got older for the next march or a future demonstration. Gloria never got to turn this dream into a reality because her life quickly went from bad to worse.

At thirteen, Gloria found herself in a mish-mash of confusing feelings and responsibilities. She knew she liked girls more than boys from a very early age, not just as friends. Awakening to her true self, Gloria felt worried and overwhelmed. If she was gay, how would anyone in her life ever love her or accept her?

The pressure of this realization demanded an escape, mainly after her mother started to suspect that something was off with her daughter. At one point, she accused her daughter of being a “dirty lesbo” and threw a kitchen knife at her. Gloria didn’t know what to do. She tried to run away but realized she had nowhere to go. The only easy escape she could find was the common escape in her family: Drugs seemed the only option left on the table.

The High Price of Addiction = The Shattering of Family Life

In the mid-sixties, Gloria had nowhere to turn as a young gay African American teen. There were no counselors in her rundown public high school, and the usual suspects overwhelmed the teachers. Although the hippies were fighting the war in Vietnam on television, they did not reach out to troubled kids in the projects. Heck, most of them never left Manhattan, except for a day at the Brooklyn Zoo or Prospect Park. The Stonewall Riots of 1969 were far away, and Gay Rights was not part of almost anyone’s lexicon. Gloria had no options.

What she did have was an aunt that shot heroin in her house with her drug-dealing boyfriend. She remembers when she first saw a bag of heroin, and she believed her cousin who told her the white powder was sugar. Sugar was expensive, and her mom seldom gave it to her brothers and sisters. Why was it in the living room in a little baggie?

Later, she saw the white powder surrounded by used needles and cotton balls, and bloody rags. She quickly learned the truth, and she loved what the drug did to her aunt and the others. It was like it took all their cares away and made them super happy. Given such a recognition, Gloria’s initial interest sunk into a deeper fascination.

At 14, she started shooting heroin with her aunt, and that first hit was like utter magic. It enveloped her in a warm bubble where nothing mattered, and everything was fine. Within weeks, Gloria was hanging out in shooting galleries with a devil may care attitude. As she told me, “I have always been a loner even when I was using drugs, and I always walked alone. I never associated with people who used drugs, except to get more for myself.”

Consequences of the Escape = Institutions, Jails, and Homelessness

Realizing that her daughter was doing drugs, Gloria’s mother decided to send her away. Gloria believes the drugs were a secondary cause. At her core, her mother could not understand Gloria’s sexuality. She hoped to find a program that would get her clean and turn her straight.

It is essential to understand that nobody else in Gloria’s family was sent away to an institution for doing drugs. Nobody else’s addiction became a reason for institutionalization. Still, Gloria knows her mother loved her. After all, she has become her mother’s number one contact with life outside of her nursing home today.

Also, Gloria sometimes wonders if the choice to send her away saved her life. Later, she still spent years homeless on the streets of Queens, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Brooklyn. Of the five boroughs of New York City, only Staten Island was spared her presence in the later depths of her addiction. However, being an addict as a teenager, the dangers are even more deadly.

When her mother sent her away at fourteen, Gloria ended up in a string of the most hardcore institutions in the state of New York. She spent the first two years in the draconian cells of the Rockefeller Program. Referred to in a study in The Journal of Social History as “The Attila The Hun Law,” these ultra-punitive measures took freedom away from and punished even the youngest offenders. Gloria barely remembers the details of what happened.

After two years in the Rockefeller Program, she was released and immediately relapsed. Quickly arrested, she was sent to Rikers Island long before her eighteenth birthday and put on Methadone. Although the year and a half at Rikers Island was bad, it was nothing compared to Albany, where they placed her in isolation for two months. The only time she saw another human face was when she was given her Methadone in the morning. During mealtimes, she was fed through a slot in her cell.

Gloria says she went close to going insane. She cannot recall all the details of what happened next, but she does know that she spent an additional two in Raybrook. A state hospital built to house tuberculosis patients; it closed its doors in the early 1960s. In 1971, the state opened this dank facility as a “drug addiction treatment facility” for female inmates. Gloria does remember getting lots of Methadone, but she does not recall even a day of treatment.

Losing Hope and Sinking into Homeless Drug Addiction in the Big Apple

After Raybrook, she ended up in the Bedford Hills prison for a couple of years. By now, she was in her twenties, and her addiction kept her separate from her family. Gloria had lost hope of a reconciliation that would only came many years later.

When she was released from Bedford Hills in 1982, nobody paid attention to her anymore. She became one more invisible homeless drug addict on the streets of the Big Apple. Being gay did not matter; being black did not matter, even being a woman did not matter; what mattered was that she was strung out with no money and no help and nothing to spare.

Although she found a woman to love, and they protected each other when not scrambling to get high, she felt she had nothing. She bounced around from park bench to homeless shelter to street corners for ten years. There was trauma and violence, and extreme abuse. Although Gloria acknowledges that it happened, she will not talk about it.

Later, after they found the path of recovery, her partner relapsed after being together for fifteen years. She went back to using, and Gloria stayed sober. It happens all the time. The question is, how did Gloria get sober in the first place?

Embracing Education Led to Freedom from Addiction and Homelessness

In the early 1990s, after a decade addicted on the streets, Gloria had had enough. Through the NEW (Non-traditional Employment for Women) Program in NYC, she discovered a way out. For the first time, it felt like people believed in her. Supported by the program, she took on a joint apprenticeship at the New York District College for Carpenters. Ever since she was a child, Gloria had been good with her hands.

In the program, Gloria thrived, learning welding, sheet rocking, floor tiling, carpentry, and window installation. Later, she is proud to say that she helped repair some historical churches in Manhattan while also being part of a crew that built a skyscraper on Roosevelt Island and revamped La Guardia Airport. For a long time, work was the heart of this woman’s salvation.

With a smile, Gloria says, “I loved that work. Those days were very exciting, and I realized that I could succeed in life at a higher level despite having a drug problem and once being a drug addict. Oh, how I wish I was out there now, working hard. There’s nothing better than tearing down old buildings and putting up something new.”

Beyond dedicating herself to work, Gloria also focused on her recovery. She also managed to reconnect with her mother. Addiction was still commonplace in the projects, and too many family members had succumbed to the disease. She could not return to that world. Instead, Gloria chose to focus on her recovery, finding meaning in 12-Step meetings and a new family.

Talking about her recovery without violating the traditions of the program, Gloria explains, “I didn’t want to take any chances, so I made sure I had two sponsors. Before making a choice, I studied each one. I saw how they carried themselves in the meetings and the people they chose to spend time with. I made sure they were walking the walk so that I could learn from them. Since I was very particular, I didn’t take chances. I knew the stakes were high. Thus, I often stayed to myself, keeping the focus on my recovery.”

From Forging a Life to Embracing a Path of Recovery 24/7

As she got older and the decades passed, Gloria embraced a 24/7 path of recovery. No longer able to do hard physical labor, she became a drug counselor. In that role, she advocates for harm reduction, needle exchange, prison reform, and decriminalization. Given her experience, she knew people would listen to her voice. Gloria did more than just get treatment after learning that she had caught Hepatitis C in the 1980s when she was sharing needles. She got certified in HCV and HIV counseling, helping others to learn how to help themselves.

Today, Gloria Harrison is very active with VOCAL-NY. As highlighted on the organization’s website, “Since 1999, VOCAL-NY has been building power to end AIDS, the drug war, mass incarceration & homelessness.” Working hard for causes she believes in, Gloria constantly sends out petitions and pamphlets, educating people about how to vote against the stigma against addicts, injustices in the homeless population, and the horror of mass incarceration. One day at a time, she hopes to help change the country for the better.

However, Gloria also knows that the path to recovery is easier today for facing all the “absurd barriers” that she faced as a young girl. Back in the day, being a woman and being gay, and being black were all barriers to recovery. Today, the tenor of the recovery industry has changed as the tenor of the country slowly changes as well. Every night, Gloria Harrison pictures young girls in trouble today like herself way back when. She prays for these troubled souls, hoping their path to recovery and healing will be easier than she experienced.

A Final Word from Gloria

(When Gloria communicates via text, she wants to make sure she is heard.)

GOOD MORNING, FRIEND. I HOPE YOU ARE WELL-RESTED. I AM GRATEFUL. I LOVE THE STORY.

I NEED TO MAKE SOMETHING CLEAR. MY MOTHER HAD A MENTAL AND PHYSICAL ILLNESS. SHE HAD POLIO AT THE AGE OF FOURTEEN BUT THAT DIDN’T STOP HER. SHE WENT THROUGH SO MUCH, AND I LOVE THE GROUND SHE WALKS ON. I BELIEVE THAT SHE WAS ASHAMED OF MY LIFESTYLE, BUT, AT THE SAME TIME, SHE LOVED ME. SHE GAVE ME HER STRENGTH & DETERMINATION. SHE GAVE ME HER NAME. SHE RAISED HER LIFE UP OVER HER DISABILITIES. SHE BECAME A STAR IN THE SKY FOR ALL AROUND HER.

BEING THAT MY MOTHER WASN’T EDUCATED OR FINISHED SCHOOL, SHE DIDN’T KNOW ABOUT THE ROCKEFELLER PROGRAM. SHE ONLY WANTED TO SAVE HER TRUSTED SERVANT AND RESCUE HER BELOVED CHILD. SHE NEEDS ME NOW AND I AM ABLE TO HELP BECAUSE I WAS ABLE TO TURN MY LIFE AROUND COMPLETELY. SHE TRUSTS ME TODAY TO WATCH OVER HER WELLBEING, AND I FEEL BLESSED TO BE HER BELOVED CHILD AND TRUSTED SERVANT AGAIN. AS YOU HAVE MENTIONED TO ME, THE PATH OF RECOVERY IS THE PATH OF REDEMPTION.

Postscript: A big thank from both Gloria and John to Ahbra Schiff for making this happen.