If you are at risk for overdose or use needles to shoot up drugs, come see Brandi and she’ll take care of you – no frills, no questions, no judgment.

On a cold November morning in 2015, Brandi Tanner and her husband stopped to pick up their 10-year-old niece from her grandmother’s house.

“Grandma’s sleeping funny,” said the little girl when they came to the door. She wasn’t dressed for school, as she usually would be at this time of morning. Concerned, Tanner and her husband stepped into the house and headed for his mother’s bedroom. They knocked on the door, but no one answered. Glancing at each other with wide eyes, they swung open the door. Grandma had rolled off the bed and her body was wedged between the dresser and the nightstand. She wasn’t breathing.

“I didn’t really have time to process that she was dead,” says Tanner. “The only thing I could think was ‘Damn, I need to call people. I need get the family out of the house so the police can take pictures.’”

Tanner’s mother-in-law had died of an opioid overdose, an increasingly common cause of death in Vance County, North Carolina. Tanner herself had previously struggled with dependence on opioids and though the years she’d seen the prevalence of addiction rise in her community.

“It was so hard to see my husband lose his mother,” she says. “I wanted to do something to help him and other people, but I didn’t know what to do.”

About a month after her mother-in-law’s death, Tanner was working at a pawn shop where she had been employed for several years. It was right before closing and she was tired. Every day people came into the shop to sell items in order to buy opioids. And it seemed like every week she received news of someone else who had lost a family member. She had just started to shut down the register when a tall stranger strode into the shop.

“There were other employees in the store but he headed straight for me like he knew I was the one who needed him,” Tanner recalls. “He walked up and asked if I wanted to help save lives from overdose. I was like, hell yeah. Where do I sign up?”

The tall stranger was Loftin Wilson, an outreach worker with the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition, a statewide nonprofit that works to reduce death and disease among people impacted by drugs. That year, the organization had received a federal grant to prevent overdose death in Vance County in partnership with the Granville-Vance District Health Department. Over the past few years, the two agencies have worked closely to increase access to harm reduction services and medication-assisted treatment in Vance County.

Vance is a rural community of fewer than 50,000 people. Driving through, one can’t help but notice large, pillared villas adjacent to dilapidated trailer parks, a scene that amidst acres of yellowing tobacco fields is reminiscent of plantations and slave quarters. In Vance County, a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line and addiction has flourished. From 2008-2013 Vance had the highest rate of heroin overdose deaths in the state: 4.9 residents per 100,000 compared to the state average of 1.0 per 100,000 (NC Injury Violence Prevention Surveillance Data). But those were sunnier days. By 2016, the heroin overdose rate for Vance County had jumped to 11.2 per 100,000. In 2017, based on provisional data, it was 24.2 per 100,000 (NC Office of Medical Examiners) and 2018 is already shaping up to be the deadliest year yet.

The chance meeting between Wilson and Tanner at the pawn shop proved to be pivotal to outreach efforts in Vance County. Wilson had years of overdose prevention experience in a neighboring county, Durham, but Tanner knew her community and everyone in it. The two teamed up and began reaching out to people in need. Driving around in Wilson’s rattling pick-up, they visited the homes of people at risk for opioid overdose to distribute naloxone kits.

The following summer, the North Carolina General Assembly legalized syringe exchange programs, and Wilson and Tanner began delivering sterile injection supplies along with naloxone. By 2018, a grant from the Aetna Foundation to combat opioid overdose had enabled them to purchase a van in which to transport supplies and to expand outreach work in Vance County.

In July 2018 I visited Tanner at the pawn shop, where she still works. Thanks to Tanner’s efforts, the pawn shop has become a de facto site for syringe exchange and overdose prevention. Walking into the shop, the first thing I notice is that Tanner packs a glock on her right hip. It’s necessary these days in Vance County, which has seen a remarkable rise in drug-related gang violence this year. In March 2018, nine people were shot over a span of two weeks in Henderson, a small town of 15,000 residents. In May, four more people were killed in less than a week, prompting Henderson Mayor Eddie Ellington to make a formal plea to the state for resources. One of the murders occurred at a hotel a stone’s throw from the pawn shop.

The danger doesn’t seem to faze Tanner. She weaves through displays of jewelry, rifles, and old DVDs as customers drop in to buy and sell. It’s a respectable stream of business for a Monday afternoon. Tanner handles the customers with ease, teasing them in a thick southern twang, inquiring after their kids and families, and discussing the murders, which more than one person brings up unprompted. She calls everyone “baby” and is the kind of person who will buy gift cards and toiletries just so she can slip them unnoticed into a customer’s bag if she knows the individual is down on her luck.

Later in the afternoon, a young female enters the shop. She and Tanner nod at each other without exchanging words. Tanner finishes up a transaction with a customer and slips out the back door. She is gone for a couple of minutes, then reappears alone. This, I come to find, is what overdose prevention looks like in Vance County.

“I used to hand out [overdose prevention supplies] from inside the shop, but people were embarrassed to come in and be seen taking them,” explains Tanner. “Now people just text me to let me know they are coming. Sometimes they come in the shop and other times I just leave my truck open out back and they get the supplies and leave.”

Henderson is the kind of town where everyone knows everyone’s business. News travels fast and so do rumors. Even though almost everyone has someone in their family using opioids, stigma still runs deep, so Tanner doesn’t advertise the exchange. Word travels by mouth: If you are at risk for overdose or use needles to shoot up drugs, come see Brandi and she’ll take care of you – no frills, no questions, no judgment. She sees a couple participants a day on weekdays and nearly a dozen every Friday and Saturday. A couple times a week she drives her truck to visit people who don’t have transportation, just to make sure they are taken care of too.

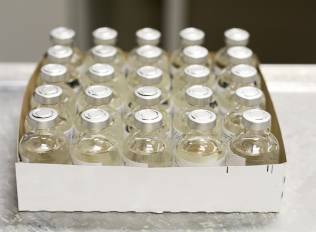

I ask Tanner to take me to her truck where she keeps the supplies, and she obliges, leading me behind the store to a dusty parking lot where her SUV is stuffed with naloxone, syringes, and other sterile injection equipment. I pepper her with questions as she moves the boxes around to show me what’s inside.

Tanner looks younger than her 35 years, but acts much older. Over the next half hour she recounts a life of homelessness, addiction, incarceration, losing friend after friend to opioid overdose, and finding her mother-in-law’s body three years ago. She relates the stories as though we were discussing the weather, completely emotionless, but still, you can tell it hurts.

“I try not to think about it,” she says with a wave of her hand when asked how she handles the trauma of losing so many people. Later, she admits that some nights she sits at home and writes down her feelings, then tears up the thoughts and throws them away.

“It’s hard not to get attached to people if you see them every week,” she acknowledges. “But I do the work because I want to help my town and my people. This is the place where my kids are growing up.”

We go back inside and I take a last look around the store. The blue-screened computers and racks of DVDs create the feeling that you’ve gone back in time, yet in some ways this pawn shop is the most forward-thinking entity in Vance County. Here, people received tools to save lives even before they were legal.

Before leaving Vance’s open fields to return to the city, I ask Tanner if she has a final message for people at risk for opioid overdose. For a moment, her voice hardens.

“I know what it feels like to not have anybody give a shit if you are here or not,” she says. Then her tone softens. “But I want people to know they are not alone. There are people out there who care and can help.”

View the original article at thefix.com