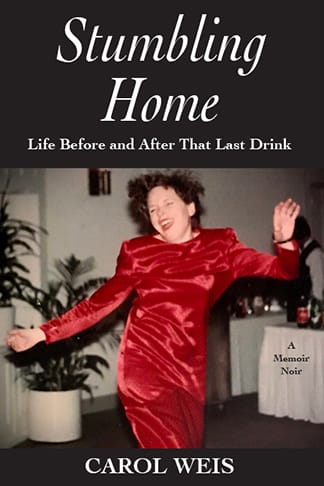

Shauna Shepard, who works as a receptionist in the local health clinic, visited with me on my back porch. She shared why she drifted into substance abuse, and how she struggled to get — and remain — sober.

After a man in my small Vermont town who had a heroin addiction committed suicide, I began asking questions about addiction. Numerous people shared their experiences with me — from medical workers to the local police to people in recovery. Shauna Shepard, who works as a receptionist in the local health clinic, visited with me on my back porch. She shared why she drifted into substance abuse, and how she struggled to get — and remain — sober.

“Drugs,” Shauna finally said after a long silence, tapping her cigarette on the ashtray. “Drugs are really good. That’s the problem. When you’re using, it’s hard to imagine a life without them. For a long time, I didn’t know how to deal with my feelings any other way. It’s still hard for me to understand that getting high isn’t an option anymore.”

I nodded; I knew all too well how using could be a carapace, a place to tuck in and hide, where you could pretend your life wasn’t unraveling.

“You can go weeks, months, even years without using, and then you smell something or hear a certain song on the radio, or you see somebody, and — bam! — the cravings come right back. If you don’t keep your eye on that shit, it’ll get you.”

“It? You mean cravings for drugs? Or your past?”

“Both,” she said emphatically. “I mean, fuck. Emotions don’t go away. If you bury them, everything comes crashing out when someone asks you for a fucking pen, and they get the last six months of shit because they walked in at the wrong time.”

I laughed. “So much shit can happen in six months.”

She nodded, but she wasn’t smiling.

I rubbed a fingertip around the edge of the saucer, staring at the ashes sprinkled over its center. “What’s it like for you to be sober?”

“It’s harder. But it’s better. My job is good, and I want to keep it. I have money the day after I get paid. I’ve got my therapist and my doctor on speed dial. I have Vivitrol. But I still crave drugs. I don’t talk to anyone who uses. It’s easy for that shit to happen. You gotta be on your game.”

“At least to me, you seem impressively aware of your game.”

With one hand, she waved away my words. “I have terrible days, too. Just awful days. But if my mom can bury two kids and not have a drug issue, I should be able to do it. When my brother shot himself, his girlfriend was right there. She’s now married and has two kids. That’s just freaking amazing. If she can stay clean, then I should be able to stay sober, too.”

“Can I reiterate my admiration again? So many people are just talk.”

Shauna laughed. “Sometimes I downplay my trauma, but it made me who I am. I change my own oil, take out the garbage. I run the Weedwacker and stack firewood. I’ve repaired both mufflers on my car, just because I could.” Her jaw tightened. “But I don’t want to be taken advantage of.” She told me how one night, she left her house key in the outside lock. “When I woke up next morning and realized what I had done, I was so relieved to have survived. I told myself, See, you’re not going to fucking die.”

“You’re afraid here? In small town Vermont?”

“I always lock up at night. Always have, always will.” Cupping her hands around the lighter to shield the flame from the wind, she bent her head sideways and lit another cigarette.

“I lock up, too. I have a restraining order against my ex.”

She tapped her lighter on the table. “So you know.”

“I do. I get it.”

*

As the dusk drifted in and the warm afternoon gave way to a crisp fall evening, our conversation wound down.

Shauna continued, “I still feel like I have a long way to go. But I feel lucky. I mean, in my addiction I never had sex for money or drugs. I never had to pick out of the dumpster. My rock bottom wasn’t as low as others. I’m thankful for that.”

I thought of my own gratitude for how well things had worked out for me, despite my drinking problem; I had my daughters and house, my work and my health.

Our tabby cat Acer pushed his small pink nose against the window screen and meowed for his dinner. My daughter Gabriela usually fed him and his brother around this time.

“It’s getting cold,” Shauna said, zipping up her jacket.

“Just one more question. What advice would you give someone struggling with addiction?”

Shauna stared up at the porch ceiling painted the pale blue of forget-me-not blossoms, a New England tradition. She paused for so long that I was about to thank her and cut off our talk when she looked back at me.

“Recovery,” she offered, “is possible. That’s all.”

“Oh . . .” I shivered. “It’s warm in the house. Come in, please. I’ll make tea.”

She shook her head. “Thanks, but I should go. I’ve got to feed the dogs.” She glanced at Acer sitting on the windowsill. “Looks like your cat is hungry, too.”

“Thank you again.”

We walked to the edge of the driveway. Then, after an awkward pause, we stepped forward and embraced. She was so much taller than me that I barely reached her shoulders.

When Shauna left, I gathered my two balls of yarn and my half-knit sweater and went inside the kitchen. I fed the cats who rubbed against my ankles, mewling with hunger. From the refrigerator, I pulled out the red enamel pan of leftover lentil and carrot soup I’d made earlier that week and set it on the stove to warm.

Then I stepped out on the front steps to watch for my daughters to return home. Last summer, I had painted these steps dandelion yellow, a hardware store deal for a can of paint mistakenly mixed. Standing there, my bare feet pressed together, I wrapped my cardigan around my torso. Shauna and I had much more in common than locking doors at night. Why had I revealed nothing about my own struggle with addiction?

*

I wandered into the garden and snapped a few cucumbers from the prickly vines. Finally, I saw my daughters running on the other side of the cemetery, racing each other home, ponytails bobbing. As they rushed up the path, I unlatched the garden gate and held up the cucumbers.

“Cukes. Yum. Did you put the soup on?” Molly asked, panting.

“Ten minutes ago.” Together we walked up the steps. The girls untied their shoes on the back porch.

“We saw the bald eagles by the reservoir again,” Gabriela said.

“What luck. I wonder if they’re nesting there.”

Molly opened the kitchen door, and the girls walked into our house. Before I headed in, too, I lined up my family’s shoes beneath the overhang. Through the glass door, I saw Molly cradling Acer against her chest, his hind paws in Gabriela’s hands as the two of them cooed over their beloved cat.

Hidden in the thicket behind our house, the hermit thrush — a plain brown bird, small enough to fit in the palm of my hand — trilled its rippling melody, those unseen pearls of sound.

In the center of the table where Shauna and I had sat that afternoon, the saucer was empty, save for crumbles of common garden dirt and a scattering of ashes. When I wasn’t looking, Shauna must have gathered her crushed cigarette butts. I grasped the saucer to dump the ashes and dirt over the railing then abruptly paused, wondering: If I had lived Shauna’s life, would I have had the strength to get sober? And if I had, would I have risked that sobriety for a stranger?

In the kitchen, my daughters joked with each other, setting the table, the bowls and spoons clattering. The refrigerator opened and closed; the faucet ran. I stood in the dusk, my breath stirring that dusty ash.

Excerpted from Unstitched: My Journey to Understand Opioid Addiction and How People and Communities Can Heal, available at Amazon and elsewhere.