Using computer modeling, researchers predicted that overdose deaths will kill 81 ,700 people in 2025 unless drastic changes are made.

Researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital have grim news about the opioid epidemic: It’s likely to continue worsening in the coming years, unless widespread, drastic policy changes are taken to address illicit drug use.

The study, published in the journal JAMA Network Open, showed that even with efforts to more tightly control access to prescription opioids, overdose deaths will continue to rise.

Using computer modeling, researchers predicted that overdose deaths will kill 81 ,700 people in 2025, most of whom will die from illicit opioids. Further restricting access to prescription opioids will only reduce that number by 3%-5.3%, researchers found.

“This study demonstrates that initiatives focused on the prescription opioid supply are insufficient to bend the curve of opioid overdose deaths in the short and medium term,” Dr. Marc Larochelle of the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center said in a press release. “We need policy, public health and health care delivery efforts to amplify harm reduction efforts and access to evidence-based treatment.”

Jagpreet Chhatwal, who co-authored the paper with Larochelle and others, said that more drastic measures are needed to target the use of illicit opioids.

“If we rely solely on controlling the supply of prescription opioids, we will fail miserably at stemming the opioid overdose crisis. Illicit opioids now cause the majority of overdose deaths, and such deaths are predicted to increase by 260%—from 19,000 to 68,000—between 2015 and 2025,” said Chhatwal. “A multi-pronged approach—including strategies to identify those with opioid use disorder, improved access to medications like methadone and buprenorphine, and expansion of harm reduction services such as the overdose-reversal drug naloxone—will be required to reduce the rate of opioid overdose deaths.”

Chhatwal said that while easy access to prescription opioids may have contributed to the crisis, today the epidemic is more about illicit opioids including fentanyl and its analogues. Because of this, efforts to reduce overdose deaths need to focus on addressing the population of people who are using illegal drugs.

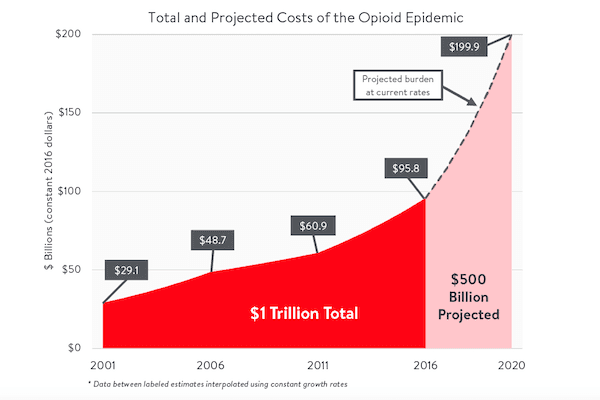

“The opioid epidemic started with a sharp increase in opioid prescriptions for pain in the 1990s; but since 2010 the crisis has shifted, with a leveling off of deaths due to prescription opioid overdoses and an increase in overdose deaths due to heroin,” he said.

“In the past five years, deaths have accelerated with the introduction of the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl into the opioid supply, leading to a continuing increase in overdose deaths at time when the supply of prescription opioids is decreasing.”