Even taking benzodiazepines in adherence to a prescribing physician’s instructions can lead to dependence.

May 30, 2019

This tip sheet, originally published in 2018, has been updated to include more recent statistics and additional information.

Benzodiazepines, a class of anti-anxiety drugs, are commonly-prescribed medications with the potential for abuse, addiction and overdose. Sound familiar? The parallels to the opioid epidemic are apparent; some physicians have taken to calling it “our other prescription drug problem” as they warn of potential dangers.

“People don’t appreciate that benzodiazepines are addictive and that people abuse them,” said Dr. Anna Lembke, a psychiatry professor at Stanford Medical School. In a phone call with Journalist’s Resource, she said that, just as with alcohol, benzodiazepines can be taken to achieve a state of intoxication.

Lembke is the program director for the Stanford University Addiction Medicine Fellowship and chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic. She has published research in JAMA Psychiatry, Molecular Psychiatry, the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, Addiction and other journals. In 2016 she published Drug Dealer, MD: How Doctors Were Duped, Patients Got Hooked, and Why It’s So Hard to Stop, a book on the prescription drug epidemic. Journalist’s Resource spoke with Lembke to learn more about the drugs and factors that have spurred current prescribing trends.

For context, a few recent studies put numbers to these trends: A new study that focuses on Sweden finds that benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-related drug prescriptions increased 22 percent from 2006 to 2013 among individuals aged 24 and younger.

A study published in 2016 in the American Journal of Public Health finds that from 1996 to 2013, the number of adults in the United States filling a prescription for benzodiazepines increased 67 percent, from 8.1 million to 13.5 million. The death rate for overdoses involving benzodiazepines also increased in this time period, from 0.58 per 100,000 adults to 3.07.

What Are Benzodiazepines?

Benzodiazepines are a class of drugs with sedative and anti-anxiety effects. A few of the most commonly prescribed benzodiazepines include diazepam (brand name: Valium), alprazolam (brand name: Xanax; street names: bars, xannies), clonazepam (brand name: Klonopin) and lorazepam (brand name: Ativan). These drugs differ with respect to how long they take to start working and how long they last, but all have similar effects, since they work by the same mechanism.

How Do They Work?

Benzodiazepines bind to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors in the brain. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter; in other words, it inhibits brain activity. Turning the power down in the brain feels like sleepiness and calm.

What Are They Prescribed For?

They can be prescribed for a number of concerns, including anxiety, insomnia and seizures.

How Can They Be Dangerous?

Benzodiazepines are accompanied by a number of side effects, including tolerance (reduced sensitivity) for the drug, cognitive impairment, anterograde amnesia (the inability to remember events that occurred after taking the drug), increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, increased risk of falls (particularly among the elderly, who, according to a study in JAMA Psychiatry, comprise the age group in the U.S. most likely to use the drugs, and use them over the long term), and, most notably, dependence, abuse and overdose. Benzodiazepines are similar to opioids, cannabinoids, and the club drug gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) insofar as the same neural mechanism underlies their addictiveness, according to research published in Nature.

Even taking benzodiazepines in adherence to a prescribing physician’s instructions can lead to dependence. Withdrawal symptoms are likely among patients who have taken benzodiazepines continuously for longer than a few weeks, according to a study published in Australian Prescriber.

For people who are looking to discontinue their use of benzodiazepines, Lembke noted that withdrawal could be potentially life threatening. “You can have full-blown seizures and die just from the withdrawal,” she said.

“The way that they’re prescribed and continued is contrary to the evidence in the medical literature,” Lembke said. She noted that the evidence indicates benzodiazepines are effective and useful only in the short term, and typically at low doses. “There’s no evidence that benzodiazepines taken long term work for anxiety,” she said. “Nonetheless, it is common practice to prescribe and continue those prescriptions for months to years to decades. Somehow there’s a disconnect between the evidence and what the practice is.”

Given These Risks, Why Are Prescriptions on the Rise?

“No one knows for sure,” Lembke said. She did, however, offer a few possible explanations.

She mentioned changes over the past three decades in the way healthcare is delivered.

As more physicians have shifted from private practice into integrated health care centers, they might feel pressure to adhere to standard protocols or perform procedures and prescribe pills like benzodiazepines, because “that’s what pays.”

She added that the way medicine is currently practiced separates patients into parts: “Patients have a different doctor for every body part … The right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is prescribing.”

Frequent changes in insurance coverage, or churn, means that individuals bounce from one coverage source (and care provider) to another. This eliminates the possibility of a sustained, caring and trusting relationship that might allow for more efficacious, long-term health interventions, Lembke added.

Other changes to the health care system have also occurred: “In many ways, doctors are like waiters and patients are customers,” Lembke explained, adding that some doctors feel the need to respond to patients’ requests and provide short-term relief or “customer satisfaction.”

A cultural shift might be at work here, too, “Patients expect it,” Lembke said. “We now think pain in any form is dangerous … We’ve also got a whole generation of individuals raised on Prozac, Adderall, Xanax thinking there isn’t anything wrong with using chemicals to change the way you feel.”

Benzodiazepines and Opioids

As Lembke pointed out, rising pharmaceutical use isn’t limited to benzodiazepines. And as the United States grapples with widespread opioid use, research points to a dangerous link between these drugs and benzodiazepines.

A study of over 300,000 patients receiving opioid prescriptions between 2001 and 2013 finds that by 2013, 17 percent also received benzodiazepine prescriptions — up from 9 percent in 2001.

Moreover, a study that looked at U.S. veterans who received opioid prescriptions finds that those who received benzodiazepines as well experienced increased risk of drug overdose death; the risk increased along with the dose. Another study finds that the overdose death rate among patients receiving opioids and benzodiazepines was 10 times higher than among those receiving opioids alone.

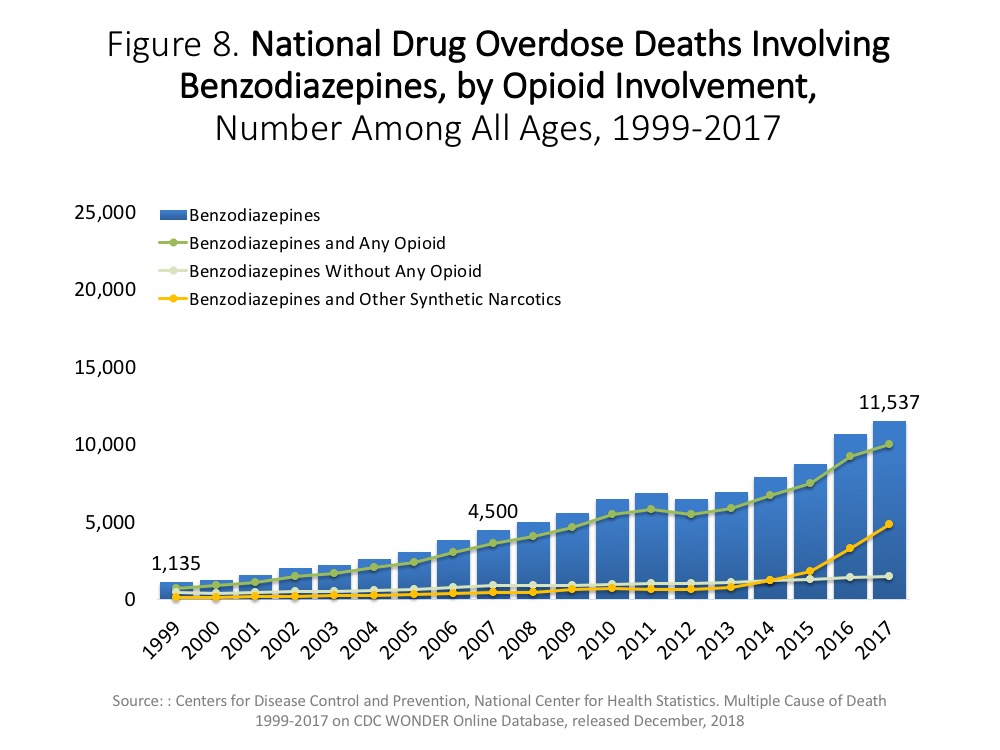

According to statistics from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), from 1999 to 2017, there was a 10-fold increase in the number of overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines in the United States — a rise from 1,135 in 1999 to 11,537 in 2017. Most of the increase has been driven by the use of benzodiazepines in combination with opioids (since 2014, the number of overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines but not any opioids has held steady). As opioids contribute increasingly to benzodiazepine overdose deaths, benzodiazepines too are increasingly present in opioid overdose deaths — the powerful combination of drugs is present in over 30 percent of opioid overdoses, NIDA reports.

Benzodiazepine abuse on its own can lead to overdose and death, but overdose deaths typically occur in combination with other substances — generally other central nervous system depressants, which, like benzodiazepines, can lead to the life-threatening effect of slowed or stopped breathing.

In August 2016, the Food and Drug Administration issued a requirement that opioids and benzodiazepines carry a black-box warning about the risks associated with using these substances together.

Now that you have the background, here are some story ideas, courtesy of Lembke:

Look into the latest wave of benzodiazepines: super-potent, designer, synthetic varieties made in illicit labs.

Investigate the growth of benzodiazepine-related patient advocacy organizations as a phenomenon.

Probe Big Pharma’s role in prescription trends and look at socioeconomic variations in benzodiazepine prescriptions (e.g., Medicaid prescribing rates).

Journalist’s Resource also has explainers on other drugs, including fentanyl and meth.

This photo, property of the , was obtained from Wikimedia Commons and used under a Creative Commons license.

This article first appeared on Journalist’s Resource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.