While the pandemic stakes might justify using hard-hitting strategies, the nation’s social and political context right now might cause fear tactics to backfire.

You probably still remember public service ads that scared you: The cigarette smoker with throat cancer. The victims of a drunk driver. The guy who neglected his cholesterol lying in a morgue with a toe tag.

With new, highly transmissible variants of SARS-CoV-2 now spreading, some health professionals have started calling for the use of similar fear-based strategies to persuade people to follow social distancing rules and get vaccinated.

There is compelling evidence that fear can change behavior, and there have been ethical arguments that using fear can be justified, particularly when threats are severe. As public health professors with expertise in history and ethics, we have been open in some situations to using fear in ways that help individuals understand the gravity of a crisis without creating stigma.

But while the pandemic stakes might justify using hard-hitting strategies, the nation’s social and political context right now might cause it to backfire.

Fear as a strategy has waxed and waned

Fear can be a powerful motivator, and it can create strong, lasting memories. Public health officials’ willingness to use it to help change behavior in public health campaigns has waxed and waned for more than a century.

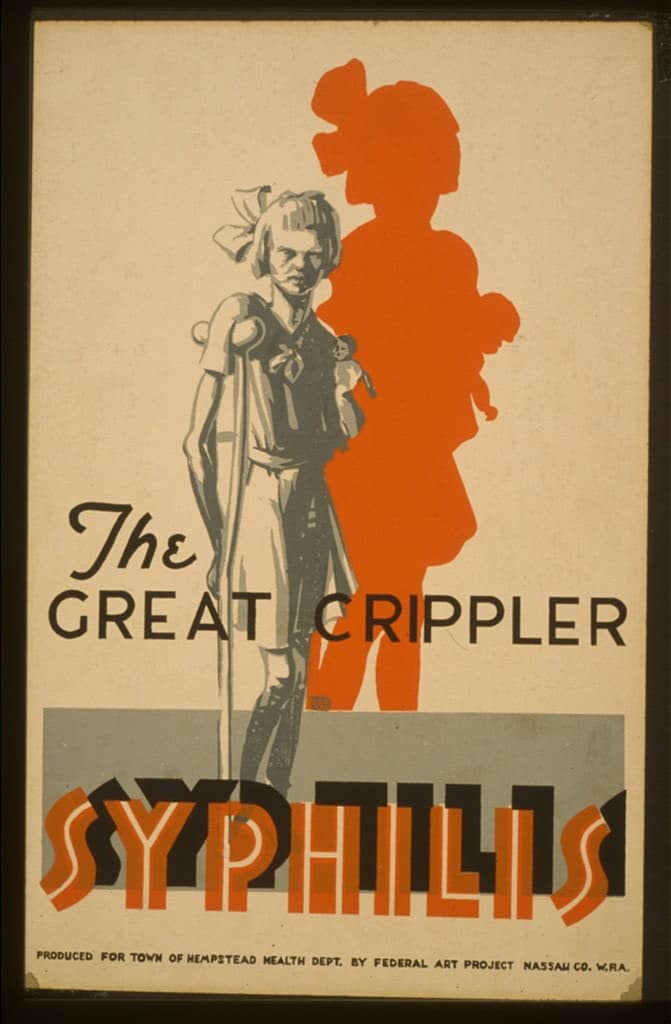

From the late 19th century into the early 1920s, public health campaigns commonly sought to stir fear. Common tropes included flies menacing babies, immigrants represented as a microbial pestilence at the gates of the country, voluptuous female bodies with barely concealed skeletal faces who threatened to weaken a generation of troops with syphilis. The key theme was using fear to control harm from others.

Following World War II, epidemiological data emerged as the foundation of public health, and use of fear fell out of favor. The primary focus at the time was the rise of chronic “lifestyle” diseases, such as heart disease. Early behavioral research concluded fear backfired. An early, influential study, for example, suggested that when people became anxious about behavior, they might tune out or even engage more in dangerous behaviors, like smoking or drinking, to cope with the anxiety stimulated by fear-based messaging.

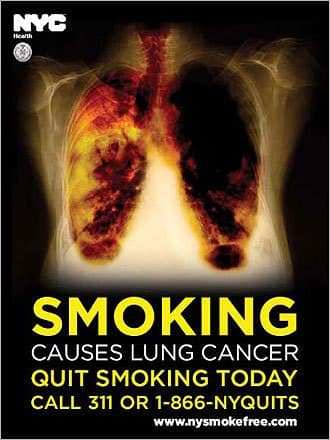

But by the 1960s, health officials were trying to change behaviors related to smoking, eating and exercise, and they grappled with the limits of data and logic as tools to help the public. They turned again to scare tactics to try to deliver a gut punch. It was not enough to know that some behaviors were deadly. We had to react emotionally.

Although there were concerns about using fear to manipulate people, leading ethicists began to argue that it could help people understand what was in their self-interest. A bit of a scare could help cut through the noise created by industries that made fat, sugar and tobacco alluring. It could help make population-level statistics personal.

Anti-tobacco campaigns were the first to show the devastating toll of smoking. They used graphic images of diseased lungs, of smokers gasping for breath through tracheotomies and eating through tubes, of clogged arteries and failing hearts. Those campaigns worked.

And then came AIDS. Fear of the disease was hard to untangle from fear of those who suffered the most: gay men, sex workers, drug users, and the black and brown communities. The challenge was to destigmatize, to promote the human rights of those who only stood to be further marginalized if shunned and shamed. When it came to public health campaigns, human rights advocates argued, fear stigmatized and undermined the effort.

When obesity became a public health crisis, and youth smoking rates and vaping experimentation were sounding alarm bells, public health campaigns once again adopted fear to try to shatter complacency. Obesity campaigns sought to stir parental dread about youth obesity. Evidence of the effectiveness of this fear-based approach mounted.

Evidence, ethics and politics

So, why not use fear to drive up vaccination rates and the use of masks, lockdowns and distancing now, at this moment of national fatigue? Why not sear into the national imagination images of makeshift morgues or of people dying alone, intubated in overwhelmed hospitals?

Before we can answer these questions, we must first ask two others: Would fear be ethically acceptable in the context of COVID-19, and would it work?

For people in high-risk groups – those who are older or have underlying conditions that put them at high risk for severe illness or death – the evidence on fear-based appeals suggests that hard-hitting campaigns can work. The strongest case for the efficacy of fear-based appeals comes from smoking: Emotional PSAs put out by organizations like the American Cancer Society beginning in the 1960s proved to be a powerful antidote to tobacco sales ads. Anti-tobacco crusaders found in fear a way to appeal to individuals’ self-interests.

At this political moment, however, there are other considerations.

Health officials have faced armed protesters outside their offices and homes. Many people seem to have lost the capacity to distinguish truth from falsehood.

By instilling fear that government will go too far and erode civil liberties, some groups developed an effective political tool for overriding rationality in the face of science, even the evidence-based recommendations supporting face masks as protection against the coronavirus.

Reliance on fear for public health messaging now could further erode trust in public health officials and scientists at a critical juncture.

The nation desperately needs a strategy that can help break through pandemic denialism and through the politically charged environment, with its threatening and at times hysterical rhetoric that has created opposition to sound public health measures.

Even if ethically warranted, fear-based tactics may be dismissed as just one more example of political manipulation and could carry as much risk as benefit.

Instead, public health officials should boldly urge and, as they have during other crisis periods in the past, emphasize what has been sorely lacking: consistent, credible communication of the science at the national level.

Amy Lauren Fairchild, Dean and Professor, College of Public Health, The Ohio State University and Ronald Bayer, Professor Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.