A music addiction is cheaper than alcohol and drugs. And not only that, it’s healthy, invigorating, fun, and liberating.

I was a disheveled and bedraggled disaster of a person back in the winter of 2012. I lived for alcohol. If beer was the entrée, crack-cocaine was my digestif. But after an intervention and rehab, I’ve been sober nine years now. I never could’ve done it without music.

Even though I had spent most of my career working in the music industry as a producer for MTV News, music wasn’t really a significant part of my life during the worst of my drinking days. But when I was a teen and again now, music has been of utmost importance. Now as an adult I realize music is better than sex.

It’s better than drugs. And it’s better than alcohol. It’s a natural high. If given a choice between music and drugs, I choose music. Starting with punk.

“Where do you go now when you’re only 15?”

Rancid, “Roots Radical,” off the 1994 album And Out Come the Wolves

I’ve always felt like a bit of an outcast. As someone who struggles with the dual diagnosis of addiction and bipolar disorder, in a way, I am. But I’m proud to be an outcast, and my punk rock upbringing only reaffirmed that being different is cool.

In the spring of 1995, March 9th to be exact — 26 years ago — I experienced my very first punk show. It was Rancid with the Lunachicks at the Metro in Chicago. I still have the ticket stub. I was 15. And in that crowd of about 1,000, I felt like I belonged. I had found my tribe. It was a moment that would transport me on a decades-long excursion, one that finds my punk rock heart still beating now and forever.

I often think in retrospect that maybe there were signs and signals of my bipolar status as I grew up. I was in fact different from the others. And I was experiencing bouts of depression inside the halls and walls of high school. Freshman and sophomore years in particular I did not fit in. I was the quiet kid who had barely any friends. I didn’t belong to a social clique like everyone else. I was a rebel in disguise. Until I found punk rock. Then I let it all hang out.

I am a Catholic school refugee. Punk was my escape from the horrific bullying I experienced in high school. Back then, the kids from the suburbs threw keggers. We city kids — I had three or four punk rock friends — were pretty much sober, save for smoking the occasional bowl of weed if we had any. We were definitely overwhelmingly the minority at school as there were probably only five or so of us in a school of 1,400. For the most part, though, we found our own fun at music venues like the Fireside Bowl and the Metro. We went to shows every weekend at the now-defunct Fireside – the CBGB or punk mecca of Chicago that used to host $5 punk and ska shows almost every night.

The Fireside was dilapidated but charming. It was a rundown bowling alley in a rough neighborhood with a small stage in the corner. You couldn’t actually bowl there and the ceiling felt like it was going to cave in. It was a smoke-filled room with a beer-soaked carpet. Punks sported colorful mohawks, and silver-studded motorcycle jackets. Every show was $5.

My few friends and I practically lived at the Fireside. We also drove to punk shows all over the city and suburbs of Chicago – from VFW Halls to church basements to punk houses.

The Fireside has since been fixed up and has become a working bowling alley with no live music. A casualty of my youth. But it was a cathedral of music for me when it was still a working club. After every show, we would cruise Lake Shore Drive blasting The Clash or The Ramones. I felt so comfortable in my own skin during those halcyon days.

Fat Mike of NOFX at Riot Fest in Chicago, 2012

Punk isn’t just a style of music, it’s a dynamic idea. It’s about grassroots activism and power to the people. It’s about sticking up for the little guy, empowering the youth, lifting up the poor, and welcoming the ostracized.

Punk is inherently anti-establishment. Punk values celebrate that which is abnormal. It is also about pointing out hypocrisy in politics and standing up against politicians who wield too much power and influence, and are racist, homophobic, transphobic, and xenophobic.

Everyone is welcome under the umbrella of punk rock. And if you are a musician, they say all you need to play punk is three chords and a bad attitude. Fast and loud is punk at its core.

They say “once a punk, always a punk” and it’s true.

Punk was and still is sacred and liturgical to me. The music mollified my depression and made me feel a sense of belonging. I went wherever punk rock took me. My ethos — developed through the lens of the punk aesthetic — still pulses through my punk rock veins. It is entrenched in every fiber of my being.

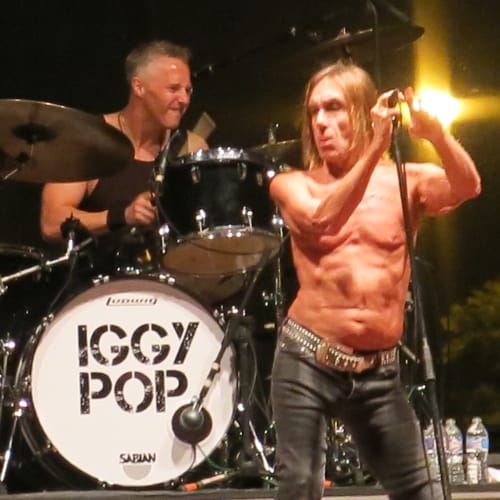

Godfather of Punk Iggy Pop at Riot Fest in Chicago, 2015

Now, whether it’s on Spotify on the subway or on vinyl at home, I listen to music intently two to three hours a day. Music is my TV. It’s not just on in the background; I give it my full, undivided attention.

I started collecting vinyl about eight years ago right around the time I got sober and I have since amassed more than 100 record albums. There’s a reason why people in audiophile circles refer to vinyl as “black crack.” It’s addictive.

I’m glad I’m addicted to something abstract, something that is not a substance. A music addiction is cheaper than alcohol and drugs. And not only that, it’s healthy, invigorating, fun, and liberating.

And while my music taste continues to evolve, I’m still a punk rocker through and through. My love affair with punk may have started 26 years ago, but it soldiers on today, even though I mostly listen to indie rock and jazz these days. I recently started bleaching my hair again, platinum blonde as I had when I was a punker back in high school. It’s fun and it also hides the greys.

Looking back on my musical self, I knew there was a reason why I can feel the music. Why tiny little flourishes of notes or guitar riffs or drumbeats can make my entire body tingle instantly. Why lyrics speak to me like the Bible and the sound of a needle dropping and popping on a record fills me with anticipation

Punk is a movement that lives inside me. It surrounds me. It grounds me. Fifteen or 41 years-old, I’m a punk rocker for life. I’d rather be a punk rocker than an active alcoholic. I’m a proud music addict. I get my fix every day.

Please enjoy and subscribe to this Spotify playlist I made of old-school punk anthems and new classics. It’s by no means comprehensive, but it’s pretty close.

The study of VA patients makes it “abundantly clear that we are not prepared to meet the needs of 3 million Americans with long covid.”

Covid survivors are at risk from a separate epidemic of opioid addiction, given the high rate of painkillers being prescribed to these patients, health experts say.

A new study in Nature found alarmingly high rates of opioid use among covid survivors with lingering symptoms at Veterans Health Administration facilities. About 10% of covid survivors develop “long covid,” struggling with often disabling health problems even six months or longer after a diagnosis.

For every 1,000 long-covid patients, known as “long haulers,” who were treated at a Veterans Affairs facility, doctors wrote nine more prescriptions for opioids than they otherwise would have, along with 22 additional prescriptions for benzodiazepines, which include Xanax and other addictive pills used to treat anxiety.

Although previous studies have found many covid survivors experience persistent health problems, the new article is the first to show they’re using more addictive medications, said Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, the paper’s lead author.

He’s concerned that even an apparently small increase in the inappropriate use of addictive pain pills will lead to a resurgence of the prescription opioid crisis, given the large number of covid survivors. More than 3 million of the 31 million Americans infected with covid develop long-term symptoms, which can include fatigue, shortness of breath, depression, anxiety and memory problems known as “brain fog.”

The new study also found many patients have significant muscle and bone pain.

The frequent use of opioids was surprising, given concerns about their potential for addiction, said Al-Aly, chief of research and education service at the VA St. Louis Health Care System.

“Physicians now are supposed to shy away from prescribing opioids,” said Al-Aly, who studied more than 73,000 patients in the VA system. When Al-Aly saw the number of opioids prescriptions, he said, he thought to himself, “Is this really happening all over again?”

Doctors need to act now, before “it’s too late to do something,” Al-Aly said. “We must act now and ensure that people are getting the care they need. We do not want this to balloon into a suicide crisis or another opioid epidemic.”

As more doctors became aware of their addictive potential, new opioid prescriptions fell, by more than half since 2012. But U.S. doctors still prescribe far more of the drugs — which include OxyContin, Vicodin and codeine — than physicians in other countries, said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, medical director of opioid policy research at Brandeis University.

Some patients who became addicted to prescription painkillers switched to heroin, either because it was cheaper or because they could no longer obtain opioids from their doctors. Overdose deaths surged in recent years as drug dealers began spiking heroin with a powerful synthetic opioid called fentanyl.

More than 88,000 Americans died from overdoses during the 12 months ending in August 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health experts now advise doctors to avoid prescribing opioids for long periods.

The new study “suggests to me that many clinicians still don’t get it,” Kolodny said. “Many clinicians are under the false impression that opioids are appropriate for chronic pain patients.”

Hospitalized covid patients often receive a lot of medication to control pain and anxiety, especially in intensive care units, said Dr. Greg Martin, president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Patients placed on ventilators, for example, are often sedated to make them more comfortable.

Martin said he’s concerned by the study’s findings, which suggest patients are unnecessarily continuing medications after leaving the hospital.

“I worry that covid-19 patients, especially those who are severely and critically ill, receive a lot of medications during the hospitalization, and because they have persistent symptoms, the medications are continued after hospital discharge,” Martin said.

While some covid patients are experiencing muscle and bone pain for the first time, others say the illness has intensified their preexisting pain.

Rachael Sunshine Burnett has suffered from chronic pain in her back and feet for 20 years, ever since an accident at a warehouse where she once worked. But Burnett, who first was diagnosed with covid in April 2020, said the pain soon became 10 times worse and spread to the area between her shoulders and spine. Although she was already taking long-acting OxyContin twice a day, her doctor prescribed an additional opioid called oxycodone, which relieves pain immediately. She was reinfected with covid in December.

“It’s been a horrible, horrible year,” said Burnett, 43, of Coxsackie, New York.

Doctors should recognize that pain can be a part of long covid, Martin said. “We need to find the proper non-narcotic treatment for it, just like we do with other forms of chronic pain,” he said.

The CDC recommends a number of alternatives to opioids — from physical therapy to biofeedback, over-the-counter anti-inflammatories, antidepressants and anti-seizure drugs that also relieve nerve pain.

The country also needs an overall strategy to cope with the wave of post-covid complications, Al-Aly said

“It’s better to be prepared than to be caught off guard years from now, when doctors realize … ‘Oh, we have a resurgence in opioids,’” Al-Aly said.

Al-Aly noted that his study may not capture the full complexity of post-covid patient needs. Although women make up the majority of long-covid patients in most studies, most patients in the VA system are men.

The study of VA patients makes it “abundantly clear that we are not prepared to meet the needs of 3 million Americans with long covid,” said Dr. Eric Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute. “We desperately need an intervention that will effectively treat these individuals.”

Al-Aly said covid survivors may need care for years.

“That’s going to be a huge, significant burden on the health care system,” Al-Aly said. “Long covid will reverberate in the health system for years or even decades to come.”

Subscribe to KHN’s free Morning Briefing.

By following the clearly outlined steps to healing in the workbook, one can start healing the emotional wounds brought on by unaddressed intergenerational trauma.

In the Intergenerational Trauma Workbook, Dr. Lynne Friedman-Gell, PhD, and Dr. Joanne Barron, PsyD, apply years of practical clinical experience to foster a healing journey. Available on Amazon, this valuable addition to both the self-help and mental health categories is perfect for a post-pandemic world. With so many people uncovering intergenerational trauma while isolated during the extended quarantines, the co-authors offer a direct approach. The book shows how to confront and ultimately integrate past demons from within the shadowy depths of the human psyche.

Addressing such a difficult challenge, the Intergenerational Trauma Workbook: Strategies to Support Your Journey of Discovery, Growth, and Healing provides a straightforward and empathetic roadmap that leads to actual healing. Dr. Gell and Dr. Barron explain how unintegrated memories affect a person negatively without the individual being aware of what is happening. Rather than being remembered or recollected, the unintegrated memories become painful symptomology.

By following the clearly outlined steps to healing in the workbook, finding freedom from what feels like chronic pain of the mind and the body is possible. Yes, the emotional wounds of childhood often fail to integrate into the adult psyche. Never processed or even addressed, they morph into demons. In response, the workbook is all about processing.

The workbook is divided into clearly defined chapters that provide a roadmap to recovery from trauma. In the first chapter, the authors focus on “Understanding Intergenerational Trauma,” providing the reader with an orientation to the subject matter while defining key terminology for future lessons. From a multitude of perspectives, they mine the depths of intergenerational trauma. Expressing with a clarity of voice balanced with compassion, they write, “Intergenerational trauma enables a traumatic event to affect not only the person who experiences it but also others to whom the impact is passed down through generations.”

The chapters carefully outline how the workbook is to be used and the psychological underpinnings behind the exercises. Moreover, they use individual stories to demonstrate the ideas being expressed. Thus, moments of identification are fostered where someone using the workbook can see themselves in the examples being presented. Overall, the organization of the workbook is well-designed to help someone face the difficult challenge of dealing with their legacy of intergenerational trauma

The chapters carefully outline how the workbook is to be used and the psychological underpinnings behind the exercises. Moreover, they use individual stories to demonstrate the ideas being expressed. Thus, moments of identification are fostered where someone using the workbook can see themselves in the examples being presented. Overall, the organization of the workbook is well-designed to help someone face the difficult challenge of dealing with their legacy of intergenerational trauma

In terms of the chapter organization, the authors make the smart choice to start with the microcosm of the individual and their personal challenges. By beginning with the person’s beliefs and emotions using the workbook, these chapters keep the beginning stages of healing contained. Afterward, a chapter on healing the body leads to expanding the process to others and the healing of external relationships. As a tool to promote actual recovery, the Intergenerational Trauma Workbook is successful because it does not rush the process. It allows for a natural flow of healing at whatever pace fits the needs and personal experiences of the person using the workbook.

In a 2017 interview that I did for The Fix with Dr. Gabor Maté, one of the preeminent addictionologists of our time, he spoke about how the United States suffered from traumaphobia. The rise of the 21st-century divide in our country came about because our social institutions and popular culture avoid discussing trauma. Beyond avoiding, they do everything they can to distract us from the reality of trauma. However, after the pandemic, I don’t believe that these old mechanisms will work anymore.

Losing their functionality, people will need tools to deal with the intergenerational trauma that has been repressed on both microcosmic and macrocosmic levels for such a long time. The pain from below is rising, and it can no longer be ignored. In need of practical and accessible tools, many people will be relieved first to discover and then use the Intergenerational Trauma Workbook by Dr. Lynne Friedman-Gell and Dr. Joanne Barron. In this resonant work, they will be able to find a way to begin the healing process.

Bob taught me that when someone reaches out for help, it doesn’t matter what you’re doing or how you’re feeling… You just go!

I’m going to miss you.

My sponsor Bob Kaplan passed away last week, on January 1st. He was my sponsor of 22 years, and I loved him terribly.

Today would have been Bob’s 37th sober birthday. He lived 77 years, the same as my father. Bob was like a father to me, I was certainly closer to him than to my old man.

***

It took me three years of daily 12-step meetings to get 30 sober days in a row. I got 29 days three different times, but I just couldn’t get over the hump, and my eskimo Steve D. had all but had it with me. He and my sponsor at the time literally kicked me out of their 12-step group… And this was no ordinary group, there were legends there like Jack F. and Bob H., true old-time heroes to many in the 12-step community.

I know what you’re thinking, how can you be kicked out of a 12-step group?

But it was the most loving thing they could’ve done. They told me I needed to go to the Pacific Group because that’s where the sickest go to get help, but first I should go to AA Central Office and speak to the manager, a man named Harvey P. Harvey reminded me of an army general with a deep raspy voice. He was going to be my new sponsor.

God bless Harvey’s soul, he took one look at me and marched me into a back office.

“You’re not for me,” he said. “You’re for Bob.”

A man who looked old enough to be my father was sitting behind a desk, leaning back in his chair with his feet up and talking on the phone. He held up his finger as if to say, I’ll just be another moment, take a seat.

Then, out of nowhere, he started screaming at the person on the phone, and then hung up on him.

Now you have to understand what the last three years had been like for me. I had a sponsor who told me I had to change everything about myself if I wanted to stay sober. And now here was this guy sitting across from me undressing someone the exact same way I would have if I was angry. I was in shock.

After he hung up the phone, his face all red and a garden hose pumping generously through his forehead, he looked up at me. I spoke quickly before he could say anything.

“Will you be my sponsor?”

As excited as I’ve ever seen anyone, he stood up and screamed at the top of his lungs, “Oh yeah!”

I don’t remember anything else from that day, but I left there with a sense of hope. I could still be me and be sober. I didn’t have to be some goody-good.

A week later I got really sick and I called Bob in the morning to tell him I was going to the doctor.

He was afraid I was going to “med seek,” so he told me to skip the doctor and go to the pet store instead and to call him when I got there.

This is like 22 years ago so I hope I’m remembering this right, but when I called him, he told me to get something called amoxicillin. I grabbed a salesperson to help me and called Bob back when I had the medication.

He told me to take two pills every four hours until they were gone.

“You know, Bob, this is fish penicillin. For fish?” I said.

“Yeah, I know what it is,” he said.

“Bob, it’s got a skull and crossbones on the packaging and says ‘not for human consumption.’ I’m no genius, but doesn’t skull and crossbones mean poison?”

“Son, I’ve got 12 and a half years sober,” Bob said. “Take it, don’t take it, I don’t give a shit. But if you want to stay sober, do what I told you to do.”

Truth be told, I don’t know if I wanted to be sober for good back then, but I loved this guy already. He was nuts, but in the best possible way. I took the fish penicillin, and I got better right away, just like he said I would.

One day shortly after that, I was so newly sober and so crazy, I drove around and around in a parking garage for 15 minutes, looking for the exit. I was lost and I just started crying. So I called Bob. He got me out of that garage in 60 seconds.

We would speak every morning and meet up at meetings and then grab something to eat. Sometimes it was just the two of us, but most of the time my 12-step brothers and sisters joined us. Bob sponsored a ton of people, and his sponsees, old friends, and his magnificent wife Signe became our extended family.

He taught me everything, everything that’s important.

He taught me that when someone reaches out for help, it doesn’t matter what you’re doing or how you’re feeling… You just go!

I got that from him!

He would say, “there’s nothing to get, only to give.”

I got that from him!

One day I called Bob while he was at work and asked him to come see a house I wanted to buy. He left work to meet me and check out the house.

Walking through the house, he says: “You got a lotta fireplaces in this place, kid, how many you got?”

“Seven.”

“This house is huge, how many square feet you got here?”

I answered all his questions, giving him the details of this great house I’d found, speaking with pride and joy, the pride and joy you feel when somebody really gets you. Then he dropped the hammer.

“Single guy, nine months sober. Do I have this right?” He asked. I nodded.

“Get in the car, asshole, I’ll show you where you’re living. I can see you can’t be left unattended.”

I got in his car and left my car behind. I did what I was told, his will was stronger than mine. It always was.

We drove back to his condo in West Hollywood and he got on the phone with his real estate agent. I can still hear him saying, “Vita, come to my house and show my kid everything in the building… He needs a new place to live and can’t be left unattended.”

I picked a unit on the same floor as his.

Every night before bed, he came over in his pajamas, slippers, and bathrobe and hung out for an hour or so screaming at the game on television if we had sports on, and eating those super spicy vegetables in a jar that he loved.

The four years I lived in Bob’s building I don’t think a day went by where we didn’t see each other. I loved him, and I miss him very much.

In 2003 I had this crazy idea that I wanted to move to Malibu. The traffic and noise from the city were just too much for me.

When I told Bob I was going to buy a house in Malibu, he told me to rent for three months before I bought anything to see if I liked it.

“Bob, how is anybody going to not like living on the beach?” I remember saying to him.

“You’re an animal, rent for three months and if you like it you can get it.”

Again, he was right! I hated living on the beach. The wind and the noise, and whether your windows are open or closed, you always wake up in the morning with sand in your bed. (I still can’t figure out how that happens?)

Instead, I bought a house about a half mile from the ocean with the most gorgeous white-water views. It was everything I loved about Malibu without the hassle of being on the beach.

Bob was also right about being in a big house as a single guy. I was used to being in a small space and this new place was giant in comparison. I wasn’t comfortable there. It was too much for me, so I turned it into what would become a world-renowned treatment center and bought a two-bedroom cottage down the street that felt much better to me.

I was not a clinician, I didn’t have any healthcare experience, and I didn’t have an MBA. I had never even been to rehab.

But what I did have was very good training. Bob lived a life of service and he taught me how to do that — in a joyful way!

There are very few people who have actually been on a true 12-step call with their sponsor, where they visit someone they’ve never met before in hopes of helping them get sober. I was so lucky to have gotten to do this with Bob.

Bob and I were sitting at Central Office together when a call came in. He picked up the phone.

Now, the people who answer the phone at Central Office are supposed to find out where the caller is, then look in the directory and give them directions to the closest meeting.

That’s not what Bob did.

He looked at me and said, “Let’s go, Rich!” We got in his car and drove to the caller’s house.

After we parked, Bob turned off the car and grabbed my arm.

“I want you to find a chair and go to the corner of the room,” he said, serious as he’s ever been. “You’re not to draw any attention to yourself and you’re not to say a word. Do you understand?”

“Yes,” I said.

“I need him focusing on me and what I’m telling him. Not a word, okay?”

“Okay.”

I don’t remember exactly what he said but I was 110% present at the time and I hung on every word.

What I noticed was his command over the room.

I noticed the empathy.

I noticed the honesty.

I learned these things from Bob. Everything that truly matters, I learned from Bob.

***

Today, Bob’s doing just fine. Right now he’s eating breakfast with his wife Signe in heaven. She’s been gone 11 months and he hadn’t been the same since.

And like any good father, he made certain that we would all be okay too. Mark, William, Big Rich, Fat Rich, and all my other 12-step brothers and sisters will be fine because our sponsor showed us how to live the right way.

This man taught me everything, and although we’re all going to be okay, the world lost a genuine hero, a great man.

Thank you, Bob. Make certain you come get me to take me to the other side when it’s time.

I love you!

In lieu of flowers, please make donations in Bob’s memory to Three Square. Read Bob’s obituary here.