With each sip I take, my brain and body scream “you freaking alcoholic,” and I know at that moment I can no longer do this.

The last drink I have is a flute of champagne.

It’s New Year’s Eve.

My husband reserves a special room for us at a nearby hotel. He buys an imperial bottle of Moet, a misplaced purchase for this particular occasion. We’re making a last ditch effort at saving our marriage. A gala’s going on in the ballroom below, where we journey to join the revelers.

Lights twinkle, streamers hang, and chandeliers glisten.

I hardly notice.

The band plays songs that were once my favorites.

I hardly hear.

Hoards of gleeful couples celebrate around us.

We dance with them, pretending to have a good time.

But I know the end is creeping near.

My husband’s been having an affair with a woman half his age. He hasn’t come clean yet, but my gut knows something’s going on. So I bleach my hair a sassier shade of blond, starve myself in hopes of losing the weight I know he hates, turn myself inside out to get him to notice me again.

But mostly I drink.

Because of my Catholic upbringing, I have a list of rules I follow.

My commandments of drinking. I only have three. Ten is too many.

1) No drinking before 5:00. I watch the clock tick away the minutes. It drives me crazy.

2) No drinking on Tuesdays or Thursdays. I break this all the time. It’s impossible not to.

3) No hard liquor. Only wine and beer. I feel safe drinking those.

Anything else means, well, I’ve become my parents.

Or even worse, his. I can’t bear to go there.

One night, when he takes off for a weekend conference, or so he says, I get so stinking drunk after tucking my daughter in for the night, I puke all over our pinewood floor. All over those rich amber boards I spent hours resurfacing with him, splattering my guts out next to our once sexually active and gleaming brass bed.

Tarnished now from months of disuse.

The following morning, my five-year-old daughter, with sleep encircling her concerned eyes, stands there staring at me, her bare feet immersed in clumps of yellow. The scrambled eggs I managed to whip up the night before are scattered across our bedroom floor, reeking so bad, I’m certain I’ll start retching again. I look down at the mess I made with little recollection of how it got there, then peer at my daughter, her eyes oozing the compassion of an old soul as she says, “Oh Mommy. Are you sick?” Shame grips every part of my trembling body. Its menacing hands, a vice around my pounding head. I can’t bear to look in her eyes. The fear of not remembering how I’ve gotten here is palpable. Every morsel of its terror is strewn across my barf-laden tongue and I’m certain my daughter knows the secret I’ve kept from myself and others for years.

You’re an alcoholic. You can’t hide it anymore.

Every last thread of that warm cloak of denial gets ripped away, and here I am, gazing into the eyes of my five-year old daughter who’s come to yank me out of my misery.

It takes me two more months to quit.

Two months of dragging my body, heavy with remorse, out of that tarnished brass bed to send my daughter off to school. Then crawling back into it and staying there, succumbing to the disjointed sleep of depression. Until the bus drops her off hours later, as her little finger, filled with endless kindergarten stories, pokes me awake.

Each poke like being smacked in the face with my failures as a mother.

His mother, a sensuous woman with flaming hair and lips to match, passes out in the car on late afternoons after spending hours carousing with her best friend, a woman he’s grown to despise. Coming home from school, day after day, he finds her slumped on the bench seat of their black Buick sedan, dragging her into the house to make dinner for him and his little brother and sister, watching as she staggers around their kitchen. His father, a noted attorney in his early years, drinks until he can’t see and rarely comes home for supper. He loses his prestigious position in the law firm he fought to get into, and gets half his jaw removed from the mouth cancer he contracts from his unrestrained drinking. He dies at 52, a lonely and miserable man.

“I know what alcoholics look like,” he says. “You’re not one of them.”

I grab onto his reassurance and hold it tight.

And with that we polish off the second bottle of chardonnay, crawl back through the kitchen window and slither onto the black and white checkered tile floor, in a haze of lust and booze, before we creep our way into my tousled and beckoning bed. It takes me another twelve years to hit bottom, to peek into the eyes of the only child I bring into this world, reflecting the shame I’ve carted around most of my life.

So on New Year’s Eve, we make our way up in the hotel elevator. After crooning Auld Lang Syne with the crowd of other booze-laden partiers still hanging on to the evening’s festivities, as the bitter taste of letting go of something so dear, so close to my heart, seeps into my psyche. A woman who totters next to me still sings the song, with red stilettos dangling from her fingers. Her drunken haze reflects in my eyes as she nearly slides down the elevator wall.

At that moment, I see myself.

The realization reluctantly stumbles down the hall with me, knowing that gleaming bottle of Moet waits with open arms in the silver bucket we crammed with ice before leaving the room. Ripping off the foil encasing the lip of the bottle, my husband quickly unfastens the wire cage and pops the cork that hits the ceiling of our fancy room. Surely an omen for what follows. He carefully pours the sparkling wine, usually a favorite of mine, into two leaded flutes huddling atop our nightstand, making sure to divide this liquid gold evenly into the tall, slim goblets that leave rings at night’s end. We lift our glasses and make a toast, to the New Year and to us, though our eyes quickly break the connection, telling a different story.

As soon as the bubbles hit my lips, from the wine that always evokes such tangible joy and plasters my tongue with memories, I know the gig’s up. It tastes like poison. I force myself to drink more, a distinctly foreign concept, coercing a smile that squirms across my face. I nearly gag as I continue to shove the bubbly liquid down my throat, not wanting to hurt my husband’s feelings, who spent half a week’s pay on this desperate celebration. But with each sip I take, my brain and body scream you freaking alcoholic, and I know at that moment I can no longer do this. When I put down that glass, on this fateful New Year’s Eve, I know I’ll never bring another ounce of liquor to my lips.

I’m done.

There’s no turning back.

And as we tuck ourselves into bed, I keep it to myself.

Each kiss that night is loaded with self-loathing and disgust.

Those twelve years of knowing squeezes tightly into a fist of shame.

Little does my husband know, if he climbs on top of me,

he’ll be making love to death itself.

Instead, I turn the other way and cry myself silently to sleep.

Your days of drinking have finally come to an end.

And you can’t help but wonder…

will your marriage follow?

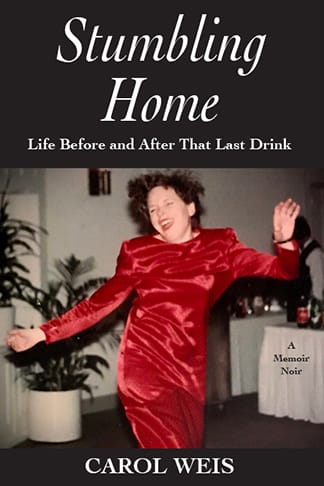

Excerpted from STUMBLING HOME: Life Before and After That Last Drink by Carol Weis, now available on Amazon.